Leigh Star

Leigh Star's Works Published in Sinister Wisdom

Remembering Leigh Star (July 3, 1954-March 24, 2010)

by R. Ruth Linden

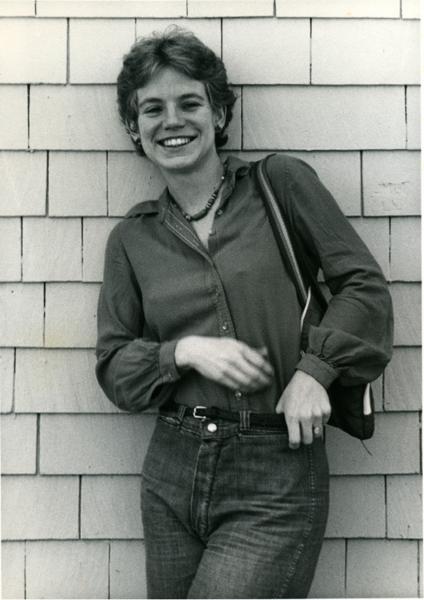

All photographs of Susan Leigh Star © Lynda Koolish

(Originally published in Sinister Wisdom 87: A Tribute to Adrienne Rich)

Susan Leigh Star, known to her friends as Leigh*, died unexpectedly in her sleep on March 24, 2010. Leigh was the founding poetry editor of Sinister Wisdom and an internationally renowned scholar in science and technology studies, feminist studies, and library and information studies. A sociologist of scintillating intelligence and playful wit, Leigh’s eye was trained, for more than three decades, on the production of scientific knowledge in a vast array of arenas from the natural sciences to computing. She was interested in ordinary – but often silenced or hidden – processes such as infrastructure, systems of standardization and classification (for example, the International Classification of Diseases), and invisible work. Leigh was the author or editor of seven books and dozens of articles and chapters; her volume of poems, Zone of the Free Radicals (Berkeley, California: Running Deer Press), was published in 1984.

In the two years since her death, Leigh’s life and intellectual legacy have been remembered and celebrated by colleagues and friends from around the world. Symposia in her memory were convened at the University of California, Santa Cruz and the University of California, San Francisco; and friends gathered for two days at the home she shared with her life partner and scholarly collaborator of 22 years, Geoffrey Bowker, in Bonny Doon in the mountains above Santa Cruz, California. Several dear friends and colleagues wrote reflections on her scholarly contributions in the months following her death.

This remembrance will not revisit the ground so ably tended by others. Instead, my comments recall the five-year period between 1976 and 1981 when Leigh was affiliated with Sinister Wisdom as a writer and editor, and provide a context for her contributions to the magazine. This is a time I remember well. Leigh and I met in Santa Cruz, where I was a student, in 1976, and developed a friendship that spanned 35 years, six states, and two continents.

Leigh joined Sinister Wisdom as poetry editor in 1978 during its second year of publication, but she was part of the magazine from its inception. Two poems, written in her early twenties, found a home in the pages of the first issue: “the rape our lack of language” and “for Jeanne d’Arc, burning.” They likely represent her first published work. Both poems are ablaze with images of patriarchal violence and the erotic. They helped to set the tone of the magazine, grounded as they were in these leitmotifs of lesbian-feminism. In “the rape our lack of language,” Leigh confronts the instructor of her freshman writing class at Harvard, who declared, “you can’t write poems about sunsets, the ocean, or love.” Here is her imagined, triumphant retort:

prick

sunsets are nonlinear Isis

squats over the water Her

thighs opening Her

great angry Uterus heaving writhing

bloody scarlet streams of clouds

sun splitting sky birthing dying

curved over latitudes

to a different dawn

a different set of suckling stars.

Leigh’s lengthy autobiographical footnote to her Jeanne d’Arc poem comments on the differences she experienced between writing poetry and writing social science theory, which she conceptualized in terms of the activity of the brain’s right and left hemispheres:

Writing my [undergraduate] thesis in psychology, for example, meant days of linear, slow connections – “logical” by the male definition of the word. Poems come in an instant, for the most part; they “brew” for weeks or years in some section of my right brain and then burst forth in a very nonlinear fashion. But there is some sharing on each side (the creative flash in theory writing or the slow reworking of lines of poetry to make them “talk” right), which gives me a hope of integration someday. I cherish both modes for myself and would like to see them appear together in my work and in my world.

During the following two years, Sinister Wisdom published Leigh’s two-part essay, “The Politics of Wholeness” and “The Politics of Wholeness II,” in which she developed a critique of New Age spiritualities based on her previous engagement with “meditation, yoga, and people who were committed to ‘natural’ life styles.” The “Wholeness” essays defined lesbian-feminism as a cognitive state – a location irreducible to politics, sexuality, spirituality, or any single constituent element. Rooted in rich, autobiographical detail – then, and always, Leigh recognized that the personal is political – and tempered by theory and analysis, the first of the essays mapped the key premises of patriarchal spiritual systems. “For me,” Leigh wrote,

the way a system of control becomes apparent is through the presence of alternative models, other worlds. The name that my other world has right now is witchcraft, which means:

I AFFIRM MY SACREDNESS/MY SEXUALITY AS THE SAME AND AS FEMALE;

I AFFIRM MY CONNECTION TO OTHER WOMEN;

I FIGHT TO SEE AND STOP ALL RAPE AND I AFFIRM MY RAGE;

I AFFIRM THE ABSENCE OF EASY ANSWERS.

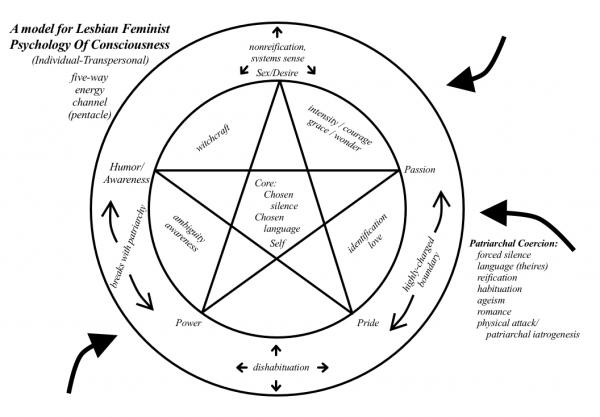

In “The Politics of Wholeness II,” Alice Molloy’s remarkable book, In Other Words, is the touchstone for Leigh’s articulation of a model of lesbian-feminist consciousness beyond the structures of patriarchal reality and awareness. In an elaborate diagram, Leigh visualized consciousness as a pentacle with a five-way energy channel at the center: a star enclosed in a circle whose five points symbolized sex/desire, passion, pride, power, and humor/creativity. Inside the pentacle, chosen silence and chosen language circled around an inner core of self. The pentacle – consciousness – is surrounded by an outer circle representing the boundary with patriarchy. A highly-charged energy field circulated between the inner and outer circles. A fluid representation, it encompassed time, mobility, love, process, and agency without reifying any of the elements of the whole. Leigh described the model as a theory, “a statement of how I perceive, how I perceive myself and others.”

The essay ends on a reflexive note in which Leigh, once again, mused on the act of writing theory:

Writing theory is for me an intense dialogue with myself: the integration of all my experience, all of my transformations. I don’t cover everything of course in writing something; but I am committed to a methodology of honor – not ignoring any relevant questions in order to impose my view of reality in a dishonest way. I see this as what “science” has proposed, but the antithesis of what it has become in men’s hands and minds.

The next year, Leigh reviewed Mary Daly’s Gyn/Ecology for Sinister Wisdom. She had studied with Mary, a feminist philosopher and theologian at Boston College, and worked as Mary’s research assistant during her undergraduate years in the Boston area. Deeply influenced by Mary’s ideas, particularly the notion of boundary dweller (an apt description of Leigh herself) and her inimitable style of word play, Gyn/Ecology prompted Leigh’s early insights on feminist methods:

Without freezing, without staticness of any sort, this book is the total confluence of method and content, of the personal and the historical, of the reach for change and the unflinching examination of suffering that I have come to know as feminism. … The naming of our own methods as feminist scholars is vital because it involves understanding our very ways of thinking, strengthening and communicating the ways we have developed for unraveling the deceptive models presented as “reality” by patriarchy …. The more we understand and can communicate about the processes by which we do our own scholarship, the more we will avoid having to unravel our own new creations.

Leigh’s thinking about the primacy of method, which she first articulated here, was a persistent thread in her writing for thirty years.

Also in 1979, Leigh guest-edited a special issue of Sinister Wisdom with the theme On Being Old and Age. Her brief engagement with issues in aging and the academic field of gerontology coincided with her Sinister Wisdom years. In 1978, Leigh had transferred from an interdisciplinary doctoral program at Stanford – a mismatch, as it turned out – to the program in Human Development and Aging at U.C. San Francisco. (She left this program after a short while as well to study sociology with Anselm Strauss, also at U.C. San Francisco, who became her mentor and lifelong friend, and completed her doctorate in medical sociology in 1983.)

Leigh’s interest in aging was linked to her experience of age nonconformity as a child and into young adulthood – something she and I shared, and a source of the deep understanding between us. This excerpt from her journal at age 14 brings the oppression of young girls to life:

To those of you who would seek to be young once again – no, you do not know that which you would have. You choose only to remember the smiles, the young body, the energy perhaps… remember also the pain, the real, real, real anguish of not knowing the unsureness the limbo the limbo… very, very rarely are young people accepted as whole people.

On Being Old and Age explored interconnections between “the bitters of youth” and the horrific isolation many elders – mostly women – face in “the concentration camps that are nursing homes,” examining how the weapon of ageism is turned on women of all ages – particularly lesbians – to marginalize, silence, ridicule, and censure. The issue also celebrated “visions of new kinds of oldness, love of the old, love of the process of becoming old, claiming the pride and wisdom of age.”

The autobiographical poem, “I Want My Accent Back,” appeared in Sinister Wisdom in 1981. This was the final issue in which Leigh had an editorial hand. After five years, Catherine Nicholson and Harriet Desmoines, the magazine’s visionary founders, turned the editorship over to Michelle Cliff and Adrienne Rich in Montague, Massachusetts and Leigh stepped down as poetry editor. In this poem, Leigh traced her path from the working class town of Lincoln, Rhode Island to Harvard College – where “I never belonged” – and back to her younger sister, Cindy (who had herself returned home after college):

My first week of college, sitting on the floor

with Andover, Exeter and Taft,

stoned, I said,

“nawh wida than a bon doah.”

Andover turns to me, be

mused: “What

is a “bon doah”? A musical instrument …?”

[…]

By 9:00 the next morning my accent disappeared. Except when I talk too fast, or to you

Though brief in duration – it spanned just three years – serving as poetry editor was a remarkable opportunity in which Leigh thrived. The magazine was robust – alive, like an organism – and Leigh had come of age as a writer. She delighted in corresponding with and publishing the work of emerging poets, like herself, alongside celebrated poets – some of whom she would later meet at conferences and other events. Her Sinister Wisdom network became woven into projects in other parts of her life, as when she interviewed Audre Lorde in 1980 in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom for an essay published in Against Sadomasochism: A Radical Feminist Analysis, which she and I co-edited (with Diana E. H. Russell and Darlene Pagano); and invited Adrienne Rich and other notable lesbians to speak on a panel she organized with the feminist philosopher of science, Sandra Harding, at the 1979 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Leigh had published Rich’s “Nights and Days” in 1978, the year that The Dream of a Common Language was released, while excerpts from Lorde’s The Cancer Journals first appeared in the special issue of Sinister Wisdom that she edited.

Leigh’s final work was an article, “This is Not a Boundary Object” and a poem, “Mourning Light: The Ethnography of Science and Love.” Science, Technology, & Human Values, a leading journal of which Leigh had been an editor at the time of her death, published them as companion pieces in 2010. Just last month, the journal’s list of “Most-Read Articles during June 2012” ranked the article #1 and the poem #5 (“based on full-text and pdf views”). Leigh would have been amused by the very idea of a most-read articles list – a marketing tactic of highly questionable meaning employed by the industry that publishes academic journals. While I don’t think she’d have taken her double standing in the top five very seriously, I’m certain she would have been pleased that her poem had reached a wide audience of colleagues in science and technology studies.

“Mourning Light” is dated Samhain eve, 2009 (also All Hallows’ Eve or Halloween), just five months before Leigh died. The poem is dedicated to her friend, Eevi Beck, on the death of her husband. The unity of the poetic and analytic modes “in my work and in my world” for which Leigh had wished in the note to her 1976 Jeanne d’Arc poem is expressed in these elegant lines:

The rape our lack of language

(Originally printed in Sinister Wisdom 1)

last night Boston November

the river flat pewter veined with light

“you can't write poems about sunsets, the ocean, or love”

explained my Expos teacher freshman year

prick

sunsets are nonlinear Isis

squats over the water Her

thighs opening Her

great angry Uterus heaving writhing

bloody scarlet streams of clouds

sun splitting sky birthing dying

curved over latitudes

to a different dawn

a different set of suckling stars.

-Susan Leigh Star

For Jeanne d'Arc, burning

(Originally printed in Sinister Wisdom 1)

in the end

the fire is all that we will see.

already its glow shames my fear of death:

I close my heated eyes,

smote against

Her indigo sky.

(listen

I have found another of us)

our life the struggle torn

and melted, wounds suspended

she too has trained to burn in silence

who moved in dry and aching quiet

who loves with deadly grace.

At every rape

at every stake

incessantly whispered into

incessantly scraped across

each of our body's sacred openings

moment by moment for all the days of our lives

We hurl molten suns

and slide and tear to kiss

containing movement

and slowly finish screaming:

We rip ourselves

into each other's blood,

a union of liquid and blazes

burnished with aloneness

there are no echoes anymore in what is named love

I speak her name clearly into your eyes

ashes melting: out

of the flames, unraped eyes

there was never

a time when

we did not know

the stakes

are high

our silence whole

you cannot hear a scream

we also wound by naming

for which we have no language we

also wound by naming tear

open to

heal

tigre mariposa*

we do not fear

your winged

poison your petalled

poise of

death

for some

now poised to perceive

with my arched uterus.

a great arc

stretches from your eyes

through my spine

across which the faintest

rustle of thought

rocks my cervix my center with

tremors which are not different from the nuzzle

and bulge of the moon

Artemis

slipper perfect silence travels between us

who knows how long I waited to feel

to see to hear

as a panther walking

picks her way

across a shelf of thin crystal glasses:

your hands lurk with that quality

soft searing pulses

poised

*Literally, “tiger butterfly”

in Spanish; the most deadly type

of Venezualan snake, whose bite

is alleged to kill in thirty seconds.

“Mariposa”, it may be noted, is

vernacular for Lesbian.

Susan Leigh star is a name I chose for myself – taking the first two which are my birth-names and the last from a special Tarot reading in which the Star came up as the card of self/highest ideals.

My writing first of all is divided up sharply – a reflection of “them”, not us – between poetry and social science theory. It's easiest for me to conceptualize the difference in terms of right brain-left brain activity: writing my thesis in psychology, for example, meant days of linear, slow connections – “logical” by the male definition of the word. Poems come in an instant, for the most part; they “brew” for weeks or years in some section of my right brain and then burst forth in a very nonlinear fashion. But there is some sharing on each side (the creative flash in theory writing or the slow reworking of lines of poetry to make them “talk” right), which gives me a hope of integration someday. I cherish both modes for myself and would like to see them appear together in my work and in my world.

I live in Somerville with March, who is often the subject, sometimes the object, and always a participant in my writing. We are radical lesbian witch spiritual sexual political personal feminists, none of which labels can beat my favorite characterization of myself as a true deviant (True deviants do not deviate from any norms – and, therefore, another name for us is “normal”).

-Susan Leigh Star

The politics of wholeness: Feminism and the New Spirituality

(Originally printed in Sinister Wisdom 3)

Susan Leigh Star

In recent years, patriarchy has expanded to accept as “normal” experiences of altered states of consciousness, meditation, dreams, yoga, biofeedback, perception-altering drugs, "enlightenment." That is, the basic structures of patriarchy have remained constant, while the repertoire of “permissible” experience has been expanded under the guise of change.

Closely allied with the above-mentioned altered states of consciousness are apparent changes in “life-style” like communal living, humanistic, transpersonal and “androgynous” interpersonal relations… again, things which are billed as leading to a better way of life, but which are ultimately imprisoning if unquestioned.

The more experiences a system expands to include without changing its basic structure, the fewer people will be able to stand outside the system and criticize it. The change required to get outside will be more far-reaching. At the same time, the system itself will provide what looks like change to most people through its own expansion.

From brown rice to lesbian separatism: one girl’s true story

Several years ago I was heavily involved with meditation, yoga, and people who were committed to “natural” life styles. I became a teacher of TM, in fact, and taught it for a couple of years. I know that I initially began these practices in an effort to heal a split I felt within myself, for which I had no name. When Zen Buddhists or Tibetan Llamas pointed out that life is an empty shell, full of illusion, something in me resonated. I did want a way to unify things, to lose my separation and isolation.

The same feelings, a little later but overlapping in time, led me to come out and begin feminist consciousness-raising. Eventually, the contradictions between woman-identification – or female completeness, self-sufficiency, and spirituality – and the male systems deepened. Starting from when I was still inside of the systems, I began to develop an analysis and a gut-level intuition of their danger and insidiousness.

The critique I offer here grows out of my experience (or that of close friends) with Zen, TM, Buddhism, Hinduism, hatha yoga, macrobiotics, and several forms of guru-following. I lump them together and, (when I'm being polite), call them “new mysticism”, “new spirituality”, or “spiritual psychologies”.

Many currently prevalent systems have similar goals (of self-actualization, unity, harmony) to the above: humanistic psychology, Jungian psychology, "personal growth groups", indeed, humanism of almost any sort. Taken broadly, this critique will be useful for these things as well.

Know thy enemy

The recent plethora of language (books, jargon, labels) for "spirituality" conveys the fact that mysticism, however watered down, is now a locus of concern/control on a mass basis. The TM movement alone claims 600,000 American initiates to their system. Beyond that, the influence of the new mysticism in general extends beyond the numbers of participants – to a point where it is incorporating itself in a major way into the Western ethos. For example, it has become commonplace to refer to something as one's “karma”, to talk about the yin or yang of something, to think brown rice is good for you, to talk about the “guru” (There are even commercials starring humorous gurus).

Fundamentally, what I mean by the terms mysticism, new spirituality or spiritual psychologies are those developmental systems which purport to lead to a higher, more "unified," or harmonious state of consciousness (nirvana, alpha states, samadhi, enlightenment, etc.) in a (more or less) structured fashion. They mayor may not have one central male figure who is the focus for disciples: Sri Chinmoy, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, Ram Dass, Yogi Bhajan, Guru Maharaji, Hare Krishna people, who provides “guidance” or a “channel” for “reaching these states” (Maybe I should just put the whole article in quotation marks).

Some systems, for example Zen and macrobiotics, do not really depend on devotion to a master, although there are male leaders. However, the lasting goal of all these systems is to eventually provide, through devotion, a technique of “purification”, meditation, etc., a permanent state of "non-duality" or oneness with the world.

For me, there is a crucial difference between duality and difference, as they apply to males, females and the constructions/perceptions of patriarchal society. My assumption is that there is a male/female difference which is at least biological, and which has been construed as a duality by males. This has given rise to philosophies and systems of dualism. Since I believe it is not possible or desirable to transcend male/female difference, I refer to transcending dualities and dualism, that is, to getting beyond the control of women at all levels. Women are the primary objects/subjects of patriarchal control. It is natural and logical [p.38] that this getting beyond is inextricably linked with, and in fact, could define, feminism.

Androgyny, or how to create a disease, patent a quick cure, and market it as enlightenment

One aspect of the state of non-dualism is supposed to be the transcendence of sex-role stereotype; the enlightened person may thus incorporate into her/his personality any qualities, those typically masculine or those typically feminine. For example, Jesus has been called an androgynous symbol by Christian theologians such as John Cobb; in Transcendental Meditation, the movement's spiritual leader may be called either Guru Dev (masculine) or Guru Deva (feminine). Buddha was said to have been “androgynous”.

Interestingly enough, this proliferation of androgynous gurus is coincidental with a new “androgynous” image being touted for Western women.

Themes of androgyny, "psychic wholeness," and transcending of sex and gender recur again and again in the new mysticism. The language used is "yin" and "yang" or feminine and masculine; the idea is that within each person are both masculine and feminine qualities, which can be “realized” (Although, most hasten to add, it just happens to be more likely that women will self-realize as mothers, supporters of men, nurturers of males; and men as active participants in the world they created).

The last time I read about the concept of androgyny, my hands began trembling with anger and I threw the magazine across the room. The magazine was Womanspirit, the article a review of June Singer's book Androgyny written by Ruth Mountaingrove:

The path to androgyny/gynandry is open to everyone: celibate, lesbian, gay man, heterosexual, whenever the urge for wholeness pushes us into the risky, long, hard work of a lifetime. The outcome is unforeseeable, bound as we are by cultural gender definitions, but surely it is more than woman, more than man. A whole person will embody both, and until this is actualized, we cannot know…

Goddness, give me the strength to say this clearly enough:

NOTHING ABOUT ME IS MALE.

I DO NOT NEED ANYTHING MASCULINE OR MALE IN ORDER TO BE WHOLE.

I DO NOT HAVE ANY MALE QUALITIES TO ACTUALIZE – I HAVE CERTAIN FEMALE POTENTIALS THAT WHILE LIVING UNDER A MALE SYSTEM HAVE NOT FLOURISHED.

I have scars and a deep anger about that in me which has been fought or raped by men, by their world. Removing the scars, the split, is my self-loving task as a Lesbian feminist.

The result will not be more than woman, more than man – but fully WOMAN for the first time. And that will come completely only with woman-identified revolution – psychic, psychological, social, material.

Overcoming the Yin-Yang duality, or, winning the war in Vietnam

Patriarchy creates and inculcates dualism. It is common for patriarchs to create needs and then manufacture a product to deal with them – like the medical patriarchs who manufacture a disease for which they must consequently find a “cure” (i.e. Thalidomide babies, vaginal cancer from DES). Since the late 1960’s, what we are witnessing in American society is the selling of a “cure” for a disease which is endemic to male-centered society – the disease of dualism, of alienation from the “true self”.

This disease has always existed, but has not always been widely perceived as the problem per se. Only a small, unusually sensitive and/or intense segment of the population ever dedicated themselves to understanding any dualism: the ahistorical phenomenon of mystics, saints, visionaries. I believe that these people always had hold of some kind of basic issue, and that that is why they were often ostracized, insulated from the mainstream of religion and society; why what they said was often misinterpreted or suppressed; why the image comes through of the mystic as a wild-eyed “crazy man” (sic). But it is important to see that the societal context within which they lived and interacted, if only the one they carried in their heads back to their cave, was male-dominated, male-supremacist, and anti-feminist. Not to ignore this would have been to generate a spiritual-political earthquake.

The union of female self-identification and mysticism is witchcraft. Politically, it has been/is ultimately threatening in its implications for the radical restructuring of man's world. It was once subjected to brutal control under patriarchy; now it is being subjected to extremely subtle control.

The kind of widespread "dealing with" issues of wholeness which we are now seeing is a kind of cooptation of the perceptions of male-identified mysticism on a very wide scale. It is being done in a manner which ensures that the connections between feminism (Lesbianism) and wholeness will not be made.

The new mystics are presenting a male-identified worldview to women who perceive the dualism in patriarchy, but who may not yet have formed their tactics for creating a non-dualistic life, a woman-centered “oneness”. They have, unfortunately, done a superb job of masking the male identity beneath a guise of androgyny (More about this below).

On a social level, these forms and controls are quite new and not yet rigidly institutionalized, but they are certain to escalate within the next couple of decades if the present trend continues.

Amidst the escalation, it is vital for us to understand that the new mysticism has to do with the control of women; that it may be seen as a sexual as well as spiritual phenomenon; that it represents a subtler form of oppression, not a form of liberation.

Without being overly simplistic, I feel it is possible to talk in quite general terms about several beliefs which all of the "new mysticisms" share, and how these beliefs function to short-circuit woman-identification:

1. Belief that by doing some technique, one can attain an ideal state.

Proust observed with astonishment that a great doctor or professor often shows himself, outside of his specialty, to be lacking in sensitivity, intelligence, and humanity. The reason for this is that having abdicated his freedom, he has nothing else left but his techniques. In domains where his techniques are not applicable, he either adheres to the most ordinary of values or fulfills himself as a flight.

– Simone de Beauvoir, The Ethics of Ambiguity

There are two kinds of problems deriving from the belief that doing a technique will bring you to an (the) ideal state of being, as the above quotation suggests. The first problem is with using a technique for growth; the second, with the function of the goal of “ideal state”.

The maxim “capture tile kingdom of heaven and all else shall be added unto thee” is the underlying basis for those mystical systems which say something like: “Just do this practice (i.e. TM, yoga, or Zazen) and enlightenment will eventually be yours”. Essentially, I have seen this idea function to absolve participants of all social responsibility for their own psychological growth “on the way to enlightenment” It fosters the belief that one can buy one's way out of the ambiguity of existence by putting in some "x" amount of time.

The logic of this concept, in simplified form, goes something like: a) we are all in an impure, unreasoning or somehow out-of-whack-with-the-universe state; b) all our actions are mediated by this disharmonious state; c) therefore, the only valid action is to meditate (or whatever the technique is) to achieve harmony and happiness. Also, as long as one is meditating, essentially one is on the right track and other things (like moral decisions and social action) will “be taken care of” in the process. It is a kind of existential cowardice, the deliberate avoidance of contradictions and decisions.

It manifests itself in such ridiculous situations as that of General Franklin Davis, who is a practitioner and ardent supporter of TM. He goes around lecturing about TM, and is often cited by other TM lecturers as an exemplar of the ability to integrate a secular career with a spiritual discipline. Obviously, Gen. Davis believes that he is developing spiritually through meditation; just as obviously, this "development" has not caused him to examine his participation in a sexist, rapist organization, the U.S. Army. I would suggest that in this case the General probably uses the fact of his involvement with TM to avoid facing his responsibility – perhaps he feels that the facet of his personality under [p.41] the heading “growth” is adequately covered by doing TM. And while the General may be an extreme example, the phenomenon varies only in degree whenever any formula is substituted for holistic change.

2. Belief that certain individuals have achieved a permanent level of insight – the ideal state.

The “masters”, in mystical traditions, are, as the label implies, generally always male. They are credited by followers with almost supernatural powers, and often function in the same symbolic fashion as the reified male-god in other religions.

In a dualistic society, it is the nature of symbols for God to represent what is good, regardless of protests to the contrary on the part of their followers (or of the symbols). Women who relate to male gurus as masters, i.e. as the epitome of good, cannot but feel themselves to be "bad" or lacking in some degree if they are trying to imitate him.

But the “master” can exercise a more insidious form of psychic control than a god-substitution. Gurus can control the language we have about wholeness – and women control themselves at this level by responding to the idea of non-duality and freedom. Gurus set themselves up to “teach” (which should be “evoke”) Selfhood and wholeness, non-dualism. They are therefore deeply desacralizing, psychically insidious for women. By blocking self-definition, they provide the ultimate substitution of male-defined reality for female self-perception.

The technique of reserving some mystical authority to a few choice men can be (and is) used to create a bureaucracy based in sexism, dealing in spiritual growth. Whatever the masters say can be used to justify any injustice or illogic on the grounds that it will help those involved get to that higher state, too. In some types of yoga, for example, the developmental schema depends on perfect love and obedience to a guru — one’s own judgment and experience are necessarily abandoned in order to be a disciple and experience “perfect love”. For women, this bears a suspicious resemblance to the self-surrender to males demanded by marriage, Christianity, etc. The masters, following what their masters taught, usually perpetuate sex-role stereotypy in the name of “it’s inexplicable, but it must be nature’s way”. Women in the TM organization, for example, are informally (secretly) disallowed from teaching meditation in prisons or mental hospitals. The rationale is that Maharishi has said that women are “more delicate” than men and couldn’t stand to be in such stressful environments.

The next premise concerns the nature of the so-called transcendence:

3. Belief that the world is fundamentally dualistic (yin-yang); this dualism can be transcended by expanding insight and perception.

The Eastern concept of yin and yang posits two basic and antithetical tensions present in all things. It is possible, goes the theory, by asceticism or meditation to transcend this duality and perceive an underlying unity. At the same time, one never really loses the aspect of being a part of the dualistic world altogether; the inner unity is incorporated into activity, the “kingdom of Heaven within” forming a solid base for “non-attached” activity on the “earthly plane”.

From a feminist perspective, this philosophical twist, which prevents mysticism from becoming an absolutely simple rejection of the world for a kind of paradise, is unconvincing. The theory is that once one arrives at this ideal-state-which-is-always-here-anyway, certain dualities are transcended. However, this process usually takes many years, and in the meantime most mystics are going about perpetuating the most basic dualism, that of sexism. Misogyny and oppression of women (and given the facts of women's oppression, “neutrality” about feminism is misogyny) do not fall away like scales with a “mystical” experience. St. Augustine, for example, who was “enlightened” by certain standards, did his share to contribute to the upkeep of gynocidal dualism in the world.

To reiterate what was said in t he introduction, it is impossible to talk about transcending duality while contributing to and failing to acknowledge the position of women as “Other” in the world. Patriarchal society inculcates duality, and in order to truly reach non-dualism it must be confronted.

The next belief seeks to avoid confrontation:

4. Belief that the world is maya, an illusion, transitory and not-to-be-invested in or attached to.

In an androcentric culture women are “sex”; we represent genital sexuality for heterosexual males. Sexuality is identified as one of the major worldly attachments and desires by mystical systems. Women, therefore, have historically represented the chief temptation of “the worldly” – that which is to be rejected, that which invites desire, which should ultimately inspire a total indifference in the mind of the true seeker. This belief is still widely held in modern systems where celibacy is recommended.

As Nancy Falk observed in an article on Buddhism , women do come to symbolize in the literature on enlightenment, “the ultimate bonds of samsara” (the world of change and impermanence). The last temptation of Buddha before his enlightenment is resisting the sexual advances of three beautiful women. When he successfully resists, he reaches nirvana.

I have seen sexism flourish within the context of asceticism and celibacy just as well as it does with the presence of sexual intercourse – heterosexuality is larger as an institution than genital relating or the lack of it.

Another aspect of the belief that the world is transitory is that it is easy to rationalize about what is so brief in the face of eternity. The responsibility for sex-based oppression is much diminished in the minds of the oppressor if the suffering of women is seen as a mere moment of pain in the fleeting reality of the world. This is an extension of trading proximate for ultimate, and thereby committing both absurdities and atrocities without responsibility.

An outcome of this interpretation of time is found in the next belief:

5. Belief in reincarnation: if you don’t make it this time around, you get to come back until you do.

The obvious result here can be one of not-doing – if you can always put off until tomorrow, literally, why do anything today? But a subtler consequence derives from a belief connected to reincarnation – the belief that you are reborn (or born at all) to finish out whatever karma you didn't do in the last life. This is (in simplified but accurate form) the basis of the whole Indian caste system: you are born and live where you deserve to be; it's all your “karma”. If you are rich, you deserve to be, etc. The only way to escape the cycle of rebirth and karma is to transcend the world as it is, usually through meditation or some other path.

This kind of Calvinistic nonsense perpetuated by ideas of Karmic Justice serves of course quite well to perpetuate the caste system according to gender. Social change itself is invalidated in such a context, as is a radical new self-defining for women. Some systems even say you have to come back as a man to be enlightened.

The following belief can also suppress positive becoming:

6. Belief that the ideal state is a universal, “natural” state.

Most mystical systems have stereotypic descriptions of the enlightened state, “ways to tell” if you're having certain advanced “spiritual experiences” – quite statically defined states of consciousness or alterations of states of consciousness. The end goals are precise, described in a linear rather than processual fashion.

And subsequently, old stereotypes about masculinity and femininity are maintained and reified. For example, a recent issue of the East-West Journal, a magazine about the new spirituality, ran an article denouncing abortion on the grounds that there are all these souls out there waiting to come back, and we can't deny them the change; women, in the new spirituality, are to be passive, maternal, devoted to husbands and “naturally” heterosexual – in order to facilitate a return to the idyllic “natural” state.

Conclusions

The women say that they have been given as equivalents the earth the sea tears that which is humid that which is black that which does not burn that which is negative those who surrender without a struggle. They say this is a concept which is the product of mechanistic reasoning. It deploys a series of terms which are systematically related to opposite terms… They joke on this subject, they say it is to fall between Scylla and Charybdis, to avoid one religious ideology, only to adopt another, they say that both one and the other have this in common, that they are no longer valid.

It is not possible to retain the old forms of these systems in a “non-sexist” way.

Men keep finding more and more subtle ways of assuring women that we can be whole, happy, fulfilled and true human beings without being political, and while continuing to give energy and primacy to men.

Most of all, they find more and more ways of assuring us that we need them, that in order to be permanently happy we need to find our “masculine complements”, whether in our heads or in a male body.

The definition of “wholeness” offered through new mysticism is bounded by male presence. Self-realizing women are not mental hermaphrodites, Earth mothers, yin, androgynes, free animae relating to their animi, “in touch with their bisexual nature”.

Another model, or Lesbianism as necessary if not sufficient condition for enlightenment

“How can I constrict this message so it will be understood uneasily?”

– Robin Morgan

For me the way a system of control becomes apparent is through the presence of alternative models, other worlds. The name that my other world has right now is witchcraft, which means:

I AFFIRM MY SACREDNESS/MY SEXUALITY AS THE SAME AND AS FEMALE;

I AFFIRM MY CONNECTION TO OTHER WOMEN;

I FIGHT TO SEE AND STOP ALL RAPE AND I AFFIRM MY RAGE;

I AFFIRM THE ABSENCE OF EASY ANSWERS.

The Politics of Wholeness II: Lesbian Feminism as an Altered State of Consciousness

(Originally printed in Sinister Wisdom 5)

Susan Leigh Star

_____________________________________________________________________

REVIEW: In Other Words by Alice Molloy Oakland Women's Press Collective, 1977

In Other Words: Notes on the Politics and Morale of Survival is a Whole Lesbian Catalogue of Delights and Challenges; one of those rare books that is a tool and a resource. For three years Alice Molloy wrote down, clipped out and annotated her own ideas and a wide range of information about consciousness, feminism, attention and the structures of “reality”. The result, thanks to the cooperation of Oakland Women's Press Collective (and hours and hours of patient typing and layout by Alice) is a book whose form and content are congruent, are nonlinear, with power to alter.

One of my goals has been to transmit information

and attitudes in a manner such that the

process its self is transmitted/received, not

just the end product. The process, a process, a

way of seeing. hearing. a way of processing.

(p. v)

There is no point in setting out a whole trip

where i say this is

my theory, here's the proof,

building up a ediface, no point in laying my trip

on people.…

it's simply because it doesn't work. it just

gives people some thing, an other thing, to build

up resistance against. and go away with enough

information to build up an opposing structure.

(p. vi)

In Other Words is an accurate title; and one of the impacts of the book is to show that “in other words” means “in other worlds”. Alice Molloy grabs the English language by its roots and shakes: how has this language structured our (patriarchal) reality? How can we pay more attention (at tension) to it?

....so we talked feminism, anarchism, and lesbianism, and discovered we were talking witch craft.

as, the craft of witches.

witch craft, the

technology of anarchy.

for example, the right to

prescribe for your self.

things got even more interesting. And

when we started talking witch craft, as

anarchist feminist lesbians, it turned

out to be paranoid schizophrenia. And

it feels good.

(p. iv)

Part of the craft of witches is learning to be aware of what is holding your attention. Alice provides instructions on how to be aware, to notice what is holding your attention: the structure of language, body language, interpersonal politics.

In the issue before last I wrote an article entitled “The Politics of Wholeness: Feminism and the New Spirituality", which criticized male systems of “spirituality” and stated that Lesbian feminism is a “necessary but not sufficient” condition for “enlightenment”.

Enlightenment is a bald and dangerous word although I did mean it quite seriously in the humorous context above. Most of me abhors writing about “spirituality” or psychic powers. I'm afraid to produce writing about instead of tools for; afraid of freezing on paper the lineaments of a world that is new and that is, above all, motion.

With this in mind I offer the following as a tool, a story and an ideal. I see it as the beginning of a map for a Lesbian feminist psychology: that is, a political awareness of our own psyche-logic that cannot be translated or symbolically imposed upon.

Introduction

The language and metaphors for the changes we experience as becoming Lesbians have often been reflections of patriarchal reality: a reality which may bend and stretch around the edges to include us as a “sexual preference” or “gay women”; as “out of the closet” or “into only making love with women”, but which cannot include us if we articulate our experience as a different and incompatible reality. One way I have found to do this is to describe Lesbian feminism as an (or the) altered state of consciousness.

To talk about consciousness is to talk about structures of awareness: energy that is channeled through paths of attention. The term “altered state of consciousness” has been used in psychology and religion to imply a very deeply changed (from some baseline or “normal” state) system of mental-physical structures.

To add the word “politics” means that the baseline from which the alterations take place is a socially-created, coercively maintained power structure.

I find it useful to think of Lesbian feminism as an altered state of consciousness in some of the same ways one would think of tripping, meditative states, hypnosis, visions or hallucinations as “alterations” of a “baseline” state of consciousness. Both Lesbian feminism and states like tripping take place outside of the everyday structures that habituate* one to living. They occur in a place where taking- for-granted stops; where ordinariness and custom dissolve.

The basic reaction from status quo society toward both of them has been that they represent a type of madness; something beyond the pale, untranslatable. Given enough time, the system tries to find a way to reduce the threat to [p.85] itself that the presence of this other world creates. Thus, for example, the initial potentials for radical change that perception-altering drugs caused were quickly ripped off into the language of humanism, love, peace and brotherhood. It became fashionable to study marijuana and LSD in the laboratories; to use the drugs to alleviate the boredom of living inside the social structures without challenging them.

Power Versus Energy

(or: I Don't Need Life I'm High on Dope)

The reason for the cooptation of these altered states of consciousness is that they remained apolitical. Drug users and meditators became alienated from the system, or perhaps decided to work to “change” it; but no one articulated what it is about the system that works to suppress altered states of consciousness, or what the cultural investment in containing those states as private individualized experiences is.

The theory that was written in the late sixties and early seventies that addressed “altered states of consciousness” (sometimes called the ‘psychology of consciousness’) leaned heavily on the idea of “energy”: tuning into cosmic energy, re-channeling psychic energy, aligning one's vibrations with the universe. Psychologists like Robert Ornstein and Charles Tart developed elaborate diagrams and explanations for how mental energy (consciousness) changes within a person's mind while under the influence of drugs or during meditation.

One key concept which underlies all theories about altered states of consciousness is quite simply that a changed state implies change from something into something else. Unfortunately this simple fact has been widely ignored among psychologists of consciousness; it is not uncommon to read whole books of theories about consciousness-altering and never find the slightest mention of what the consciousness has been altered from. What is missing, of course, is an exploration of the “normal” state of consciousness; the very thing that is so taken for granted that it is nearly impossible to see.

Tart mentions the baseline state of consciousness in his work, and I think he does intuit the importance of exploring its dimensions in order to chart changes from it. But he never does more than mention its existence, and never its content.

By designing theory which purports to explain changes of consciousness, but which ignores who invests in the status quo and how they teach us to ignore cosmic energy in the first place, the psychologists and philosophers of altered states of consciousness contribute to the idea that the authorship of reality is arbitrary. Tart could even make the following statements about the “social construction of reality”:

One of the greatest problems in studying consciousness and altered states of consciousness is an implicit prejudice that tends to make us distort all sorts of information about states of consciousness. When you know you have a prejudice you are not completely caught by it, for you can question whether the bias is really useful and possibly try to change it or compensate for it. But when a prejudice is implicit it controls you…

The prejudice discussed in this chapter is the belief that our ordinary state of consciousness is somehow natural. It is a very deep-seated and implicit prejudice.

(States of Consciousness, p. 34)

I stress the view that we are prisoners of our ordinary state of consciousness, victims of our consensus reality, because it is necessary to become aware of this if we are to have any hope of transcending it, of developing a science of the mind that is not culturally limited.

(States of Consciousness, p. 48)

And then use the generic “he” all through his writing; and not hint that consensus reality requires a consensus – real people who believe in the prejudices mentioned above, and who react when those prejudices are challenged. He assumes that reality-creating and maintaining is arbitrary, and that “transcending” it can be done apolitically.

As a Lesbian feminist, I make no such assumption. I want to examine the politics of reality maintaining, and answer the following questions:

In whose interest is it to maintain the consensus reality? If we are “prisoners”, who is guarding the prison and what means of coercion are used to keep us there? Who threatens the existing created reality? Why, and under what conditions? What is involved in creating an alter* reality?

I want to name names.

Patriarchy as a state of consciousness and a consensus reality has depended upon the silence of Lesbians

It's vitally important that we begin to name (and therefore create and strengthen) our reality-changing for the depth change that it is. In order to talk clearly about our changes and possibilities, we need a language that can say in no uncertain terms: this new world challenges everything. Its potential goes as deep as perception itself, as wide as a totally new political structure. When seen from the baseline, it throws us into madness, into chaos, into an other world.

Language is like an oil that slips through consciousness and its attendant structures; almost imperceptible while the machinery is working unquestioned. Lesbian feminism is an alteration from the structures – linguistic, neurological, emotional, historical, physical – that reflect our experience back to us and which we are coerced into accepting through “female socialization”.

Perception, Cognition and Lesbianism

My favorite sign in the Gay Pride March in San Francisco read: “Lesbianism is More Than a Sexual Preference”. As I mentioned above, one of the ways that we are tolerated is to be defined as women with tastes that run a little counter to the usual. Women who have certain feelings the origin of which may be uncertain but which can be included in the smorgasbord of sexual “preferences” that “happen” to “people”.I propose that there is a vital component of Lesbian feminism that has been theoretically ignored in descriptions of the “etiology” of Lesbianism: a perceptual, cognitive [p.87] component. I think that Lesbian feminists see and think things that are counter to patriarchal descriptions of reality, as well as feeling that which is forbidden.*

The implication of this view is that Lesbian feminism is created as an altered state of consciousness (cognition, perception) by women who are willing to question the perceptual bases of our worlds. It doesn't just come out of feelings, or just out of political analysis.

And when something “happens” that is an alternative to a coercively enforced social structure (heterosexuality in this case), it doesn't happen without someone making it happen, making decisions, saying no to coercion, resisting, creating. I don't just prefer to do something that requires a challenge of reality to do; and when I give language to my reality-challenging, I destroy old worlds and create new ones.

Whenever a Lesbian writes or speaks about herself it is a political act, because it is our silence that has underpinned patriarchy for centuries. Because we do not fit into patriarchy's basic structures, our language has both the power to shatter and to expose. Conjoined, the words of Lesbian feminists represent the politicization of the deepest structures of consciousness.

Women have been driven mad, “gaslighted” for centuries by the refutation of our experience and our instincts in a culture which validates only male experience. The truth of our bodies and our minds has been mystified to us. We therefore have a primary obligation to each other: not to undermine each other's sense of reality for the sake of expediency; not to gaslight each other. Women have often felt insane when cleaving to the truth of our experience. Our future depends on the sanity of each of us, and we have a profound stake, beyond the personal, in the project of describing our reality as candidly and fully as we can to each other.

– from Adrienne Rich's Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying.

When I speak directly I feel it throughout my whole body. The sensation of not translating is quite distinct; a new experience for me. As most of us, I have always been a Lesbian a witch a madwoman inside. But until I began to speak directly (and can't always do that all the time yet) from that experience, it was not empowered with reality. It had neither the power to be reality or to challenge the static reality handed to me growing up.

Naming the Content of Lesbian Feminist Consciousness

By “state of consciousness” I mean something more precise than mood, feelings, or passing perceptions. A state of consciousness is “a unique, dynamic pattern or [p.89] configuration of psychological structures, an active system of psychological subsystems”. Although each of the substructures, or any of them, can change from time to time, the overall patterns of a state of consciousness remain recognizably the same.

The unique, dynamic configuration of consciousness that is Lesbian feminism is both individual (personal) and generalizable as a recognizable common state of consciousness (political).

In order to more clearly communicate an “alter reality”, I'll describe how I conceptualize several matrices or components of my own awareness/consciousness. They are names of parts of myself; a personal/personal configuration. But they are also me as a Lesbian feminist witch spiritual sexual political, etc. The names are drawn from common experience, and perhaps can reflect back out toward that experience for other womyn.

The matrices are layered in varying thicknesses around a core of silence and language, of inner “space” (sometimes that I'm aware of, sometimes not) and are constantly shifting, in motion. They are political, real, and material.

1. language, which encircles and roots in all the others

2. habituation (awareness and attention)

3. intensity/courage/time

4. nonreification/systems sense/ambiguity

5. relationship to patriarchy

6. witchcraft/psychic tools/history

7. identification

8. physical being

9. love/romance/sex

10. grace/wonder

Notes for the Model:

This is my visual conceptualization of Lesbian Feminist consciousness. At the center is a five-way energy channel whose five points symbolize Sex/Desire, Passion, Pride, Power and Humor/ Creativity (self-perspective). I’ve found it useful to think of these as parts of a system without confounding them. The points circle around an inner core of Self, chosen silence and chosen language. The outer circle represents the boundary of our consciousness with patriarchy: the inner arrows suggest mobility and a highly-charged energy area. The outer area, patriarchy, is symbolized by the larger arrows (coercion).

The reason for the “individual-transpersonal” notation on the top of the chart is that while this model is drawn in terms of an individual womyn’s psyche, it is also a composite of womyn’s (Lesbian feminists’) consciousness as I've perceived it in a general way. This, like any theory, is a statement of how I perceive, how I perceive myself and others.

Because of my limitations in drawing, the model is frozen in time and space. Remember while looking at it that an accurate model would have many thousands of circles overlapping and in different relations to patriarchy and to each matrix.

The chart above shows that several of the matrices have a boundary-maintaining or filtering aspect as well as a creative aspect. The chart can't grasp the element of time or of social interaction, the changing layers and dimensions of consciousness, but should be imagined within patriarchy as a mobile and creative strategy for its destruction. At the same time, it is affected by its presence wilhin that coercive social structure, and thus is historically placed in the present, at a time when our social reality is still precarious.

Below, I describe the function/structure of each of the matrices – again, they can only analytically be separated. In reality, they function as an interlocking system, irreducible.

Language

… the fundamental coerciveness of society lies not in its machineries of social control but in its power to constitute itself and to impose itself as reality. The paradigmatic case of this is language.

To deny reality as it has been socially defined is to risk falling into irreality, because it is well-nigh impossible in the long run to keep up alone and without social support one’s own counter-definitions of the world. When the socially defined reality has come to be identified with the ultimate reality of the universe, then its denial takes on the quality of evil as well as madness.

(from The Sacred Canopy)

The first and most important matrix is language. As far as we can extend language is as far as our imagination goes.

The first and most important matrix is silence. As far as we can extend silence is as far as our imagination goes.

Language arises from necessity and from power: the need to name and the political power to do so. The need and the power function together to shape a reality bounded by the language. The worlds, the realities are not contained in the language; rather, the language reflects and in turn shapes them in a changing and systemic way. The farther limits of language are thus the farther limits of reality, but neither is causal. If the language incorporates and reflects mobility, change, and non-reification (i.e., Lesbian feminist language) the reality need not be “bounded” in the usual sense.

Unchosen silence can come from either a lack of language or a lack of hearer. As Lesbians we have experienced all three: lack of language, lack of audience, lack of both words and listeners.

The three lacks produce different kinds of madness, madnesses which are maximized and accentuated by patriarchy in historically changing patterns.

Time

Marking the passage of time in new ways could be a method of uttering ourselves. Celebrating solstices and moon phases instead of Christ's birthday and wartime victories and capitalist work-weekends; expressions of rage and power on the anniversaries of things like the banning of The Well of Loneliness or the vandalism of Diana Press; honoring menarches and menopauses.

Dreams

Dreams can provide new language. I had a dream of a world in which there were only three words to describe different ways of being:

labyris – cutting, incisive, warrior-womon;

labyrinth – complex, weaving in and out, mystery;

labia – unfolding, wonder, gentleness;

from which I wrote this poem:

labyris

labia

labyrinth

Artemis

I have dared to spin your name into the small hollows

tucked beside my cervix

I have plaited your open soul between my hands

labyrinth

labia

labyris

my core of language.

am Amazon,

left breast unscathed.

speaker and essence

this truth leaps from my brain:

we are the first and last structure of madness;

its constituent form.

And from our silence

are woven all the cycles in which madness

articuLates

its nature.

We re-order priorities, we choose to use certain words more and more frequently. We name what we use, what we have, what we care for. It begins with the body, reclaiming territory, and extends to the imagination, creating territory. Monique Wittig’s The Lesbian Body is thus a stake in “irreality”, in madness that way: an initial defining of territory, hitherto silenced.

Getting down to the nitty-gritty of changing the language we are habituated to is a collective undertaking. Here are a couple of instances I have experienced.

Names

Are you allright?

Do you sleep at night?

Do you have enough time

to use your mind?

Do you remember

your own name?

– Meg Christian

Our names are basic. I took back a great deal of strength and power when I decided to choose my own name, and can still be reminded when I use it that it is a symbol, an aspiration, a source of self (the Star is a Tarot card representing integration of inner and outer, dreams and action).

The names that womyn choose represent a rite of passage into Lesbian feminist culture; a refusal of the naming of the child (non-person) by the adult (in power), and of the womyn and children by the father.

Habituation (Attention and Awareness)

“What holds my attention has my energy”.

(lOW, p. 5)

We are habituated to patriarchy. Femininity is a habit – learned.

In psychology, habituation is a precise term that applies to the inability to perceive a stimulus after it's been presented to you a number of times. Your brain waves literally flatten out and stop responding to it after a short period of time.

There are Zen monks who have trained themselves, by controlling their attention patterns (maintaining their awareness), never to habituate to anything. In other words, they notice every time a stimulus is presented to them. In one experiment, a tone was presented to them a number of times and their brain waves registered at the same intensity each time. Subjects without the training became habituated to the tone quickly; within three or four times, they stopped being able to really notice or perceive the tone.

I have always been particularly struck by this experiment. I know the one way “they” can really get to me is to bore me to death. Patriarchy produces an endless drone of empty words, of sameness, of contentless messages that have linear and monotonic rhythms. I usually “tune out” the messages, try to ignore them in order to have some sanity. But I'm actually not convinced that this is the best thing to do – the drone does take some of my energy even by doing this. The hum and buzz of noise, even where I do not perceive it as sound (i.e., as meaningful), requires a portion of my attention. And, like it or not, some of the messages do get in. Am I more well-guarded if I try to ignore them, or if I can pay a controlled amount of attention to them and not be drugged by them? A further lesson to be learned from the Zen monks is that while they noticed each tone, and registered it in their brains, they did not physiologically react much to each tone. In other words, they knew precisely (i. e., just so much but not more) what was being presented to them, but were not affected by it beyond the noticing.

the rhythm, the beat, the tempo, if it is

different from mine, i will begin to feel

agitated. or, i can be lulled into the other

rhythm. babies are lulled to sleep more openly, the

lulling to sleep of adults is more covert

(lOW, p. 8)

Calmly, lucidly, I repeat (and I cry, and I rail, and I pronounce, and I explain, by speech and by writing, to the end): I believe in the generality in the profundity, of the fact of misogynism: yes, always and everywhere, in the home of the capitalist, or of the proletariat… I believe in phallocratism at every second, of everyone, in each class and each country…

The fact of misogynism, as with all repressive relations, is not created from the good will of Tom, Dick and Harry. It stems, cruelly, from individuals. It is the starting point for institutions, it maintains mental structures. One will not be able to understand the feminine state of wretchedness if one does not fundamentally grasp it as such: a community, historical, general, daily, world-wide phenomenon, a fundamental relation between women and non-women….. It affects all cultures… it is at once the most intimate of our particular life and the most common of our collective. It is the air we breathe.

– Le feminisme ou La mort (Feminism or Death) by Francoise d'Eaubonne (my translation)

I think the most strategic survival skill is to neither be agitated by the input of patriarchal energy nor to be lulled into ignoring it. We should know precisely what is being put out at us; and I am not saying to defect from our anger or to “plan” our responses. We must learn not to let them deploy our attention into mindless structures; and learn to turn our own attention into mobile, political, exciting structures.

Language

Alice speaks of “becoming literal” as a way of counteracting the lulling effect of patriarchal language. Good examples of what she means by literalness can be found in Alice in Wonderland – much of the humor of the book hinges on taking the metaphors of language literally.

Going into the puns, as well as into the etymology of the language, does help to dishabituate from it. For example, Alix Dobkin takes a step away from the language by emphasizing the “coincidental” construction of certain words:

if we don't let maneuvering keep us apart,

if we don't let manipulators keep us apart,

if we don't let manpower keep us apart,

or mankind keep us apart

we've won –

what i mean is

we ain't got it easy –

but we've got it.

(from “Talking Lesbian”, Lavender Jane Loves Women)

and so doing refuses to partake of a linear or “serious” same form refuting of oppression.

Which turns into my next point, that another way to sidestep boredom is to put our arguments into surprising form:

Humor

Humor is a way of confronting people indirectly – of dishabituating them. Patriarchy has used ridicule and reduction to cripple us and stop us from taking ourselves intensely; but we use humor to defend ourselves from being lulled into their structures.

Humor consists essentially in being outside of ordinary structures. An apocryphal story was circulating at one point when Susan Saxe gave her T.V. message: “I will fight on as a womon, a Lesbian and an Amazon” – the FBI had seized on the word “Amazon” and was frantically running it through their computers, trying to decode the “secret message” Saxe had presented to the womyn of the world.

“Your friend is not a warrior”, he said. “If he were, he would know that the worst thing one can do is to confront human beings bluntly”.

“What does a warrior do, don Juan?”

“A warrior proceeds strategically”.

“I still don't understand what you mean”.

“I mean that if our friend were a warrior he would help his child to stop the world”.

“How can my friend do that?”

“If one wants to stop our fellow men one must always be outside the circle that presses them. That way one

can always direct the pressure”.

(Journey to Ixtlan)

To be outside the circle that presses them.

To be authors of our own open circle.

Intensity/Courage/Time

“The thing to do when you're impatient,” he proceeded, “is to turn to your left and ask advice from your death. An immense amount of pettiness is dropped if your death makes a gesture to you, or if you catch a glimpse of it, or if you just have the feeling that your companion is there watching you…”

He replied that the issue of our death was never pressed far enough. And 1 argued that it would be meaningless for me to dwell upon my death, since such a thought would only bring discomfort and fear.

“You're full of crap!” he exclaimed. “Death is the only wise advisor that we have. Whenever you feel, as you always do, that everything is going wrong and you're about to be annihilated, turn to your death and ask if that is so. Your death will tell you that you're wrong; that nothing really matters outside its touch. Your death will tell you, I haven't touched you yet."

(from Journey to Ixtlan)

We have refused, or begun to refuse, a great deal of the institutionalized death that is dealt to womyn. We feel it so deeply when we see other women accepting the death: a gutlevel horror of living death.

Claiming one's intensity is a profoundly feminist act. We each have a history as Lesbian feminists of being told not to take it all so “seriously, dear” – I'm certain. “You can't have everything”, they say. But as Lesbians we refused to settle.

Why we did not settle is a better etiological question to ask about Lesbians than “how did this pathology occur?” But the most useful question for us is: how did we not settle? Each of us has extricated herself from some or all of the gender system, and each of us has had (and some of us nearly alone) to figure out a strategy for doing so. What were the strategies?

When asked once why certain people were self-actualizing, psychologist Abraham Maslow couldn't answer. He finally came up with something called the “chutzpah factor”: an extra bit of spunk coming from no one knows where.

We need to name the silent strategies by which Lesbians have used our chutzpah factor to affirm self: to name, share and teach it as resistance to bullshit; the power to question authority; the refusal to settle for less.

Age/Aging/Ageism

One of the heaviest tactics of muting our intensity and courage is anchoring and imprisoning the way we perceive age and aging. Ageism and sexism/patriarchy stand in incredibly complex relation to each other, and there isn't space here to more than mention it. The motif I carry in my mind is that men have found it necessary to reduce the three- fold nature of womyn – Virgin, Crone and Mother – which was once found (or could be found) in all wimmin at all times to only one or another, frozen in time.

An essay/story by River Malcolm helped me imagine the consciousness-shattering/building possibilities of an ageist-less world:

They say we do not occupy a part of time, that each of our lives is a consciousness which extends through the whole of time. Each of our consciousnesses is a way of knowing, a knowledge, a conception of the whole of time. Therefore there are many times, and not one. Therefore we are each elder to the other.

They say elder is the term of greatest respect, with which we remind ourselves that we are listening to a sovereign and separate truth which we can never reduce or contain within our way of knowing…

(from "The Women Talk About How They Live")

Nonreification/Systems Sense/Ambiguity

The women say that they perceive their bodies in their entirety. They say that they do not favour any of its parts on the ground that it was formerly a forbidden object. They say that they do not want to become prisoners of their own ideology.

(from Les Guerilleres)

To form a movement that is really movement. By questioning every assumption, a really mobile vision.

To build into our ideology a nonreification clause:

one must have a vision:

but then put the vision

out of the way. so to speak. of the vision

that is actually created

(step by step) in the outer

world. Otherwise, the vision

blocks the vision.

(IOW, p. 41)

In 1948 Simone de Beauvoir wrote The Ethics of Ambiguity – an incisive statement of the sameness of all political formulae and how they interact with the psychology of the individual. She proposes there a mode of politics that sidesteps simplicity without negating political action; a way of creating a vision, as the quote from In Other Words suggests, while not idolizing the vision or proselytizing for it.

Lesbian feminists are uniquely advantaged to opt for ambiguity, complexity, mobility, change. Balanced on the edge of patriarchy, we see the danger of falling into it, or falling out of it into a mirror image of it. Mary Daly's concept of “boundary dwelling” describes a high-energy state, an interface which demands constant self-scrutiny and change, motion. And maintaining an ethics of ambiguity also requires a systems sense – seeing that all the parts work together; anyone thing affected affects the whole system. The personal is the political is the everything else. Patriarchy is systematic: thorough, one by one, linear. Feminist analysis is systemic: of the whole, nonlinear, from the perspective of the outsider.

TO BE (left brain) AND NOT TO BE (right brain)

THAT IS THE ANSWER.

(IOW, p. 58)

Maintaining the vision, opting for complexity is difficult and exhausting. All of us have been trained to think in terms of simple solutions, formulas which produce cause-and-effect changes.

Much of what is narrowly termed “politics” seems to rest on a longing for certainty even at the cost of honesty, for an analysis which, once given, need not be re-examined. Such is the dead-endedness – for women – of Marxism in our time.

Truthfulness anywhere means a heightened complexity. But it is a movement into evolution. Women are only beginning to uncover our own truths; many of us would be grateful for some rest in that struggle, would be glad just to lie down with the sherds we have painfully unearthed, and be satisfied with those. Often I feel this like an exhaustion in my own body.

The politics worth having, the relationships worth having, demand that we delve still deeper.

(from Women and Honor: Some Notes on Lying)

To reify any part of our complex vision is to jeopardize both our honor and our viability as a world.

Relationship to Patriarchy

the awareness of rape

spoken or unspoken, the

threat of violence

____________________________

lies at the periphery of my consciousness during even the simplest act

the line between rape and rapefreedom

circumscribes our lives. We must begin to image/imagine a world where rape is unthinkable, impossible.

The idea that the perceptual interpretations that make up our world have a flow is congruous with the fact that they run uninterruptedly and are rarely, if ever, open to question. In fact, the reality of the world we know is so taken for granted that the basic premise of sorcery, that our reality is merely one of many descriptions, could hardly be taken as a serious proposition.

It has been important for me to begin describing patriarchy (the system wherein rape is possible) to myself as a constructed reality; as one of many possible descriptions of the world. But again, not as an arbitrary description: someone(s) authored and continue to author (an ongoing verb, not one-time) the structures. Invested in, authored by, those who profit from it.

we should at least understand just what it is the system has been doing to us, and the extent to which they are getting better at it. “better” doesn't begin to describe it; they are making a qualitative leap in their ability to keep us locked in our places.

definitely a challenge. an occasion to rise to.

(lOW, p. iv)>

I think that how we conceptualize ourselves in terms of fighting or “trying to change the world/create a new one” is vitally important. One of the values of thinking about our lives as altered states of consciousness is in helping us to conceive the outrageous, the unthinkable, the mad: the very things that will surprise them. In terms of our own consciousness, we must become chameleons, quick-change artists, while avoiding deception and lack of identification with ourselves. For a long time now I have thought in terms of guerrilla warfare; that I am a resistance fighter. What we are facing is a massive war being waged against us at every level (physical, moral, psychological and spiritual), and in that context it is difficult to talk about the “ideal” shape of a “politically correct” plan of action. I feel the need to give full credence to our battle scars, to trusting that each of us will do what she can where she is with the tools that she has (Not to ignore the possibility of coopting or pouring our energy out for nothing; not to ignore the utter necessity for visions and possibilities).

What I am saying here is that what I am habituated to is precisely what makes me dangerous to myself and to other wimmin, and also what makes me predictable in terms of the system. I cannot imagine myself out of patriarchy in terms of wishing away the violence and the brainwashing; but I must imagine myself out of patriarchy in order to know what my bottom line is, and how to make it bottomer.

The more serious (and Less Serious) I become, the more ways I become alter in the deepest sense with relation to patriarchy, and at the same time alter with relation to old selves. Thus, the ways we do that are both individual and political; for me, writing theory is a way of envisioning (en – to place within; vision – placing my perception within a vision). The theory I wrap with alter visions is a weapon/ tool/defense/grace and meaning.

Witchcraft/Psychic Tools/History

I take the word witch as seriously as the word Lesbian in talking about myself. Historically and politically, the word has had many meanings: as a female-centered religion, as an ancient form of social organization based on agricultural and lunar cycles, as a resistance to patriarchy/Christianity, as healer, wise womon, as knower and user of psychic skills/power.