Review of In the Dream House by Carmen Maria Machado

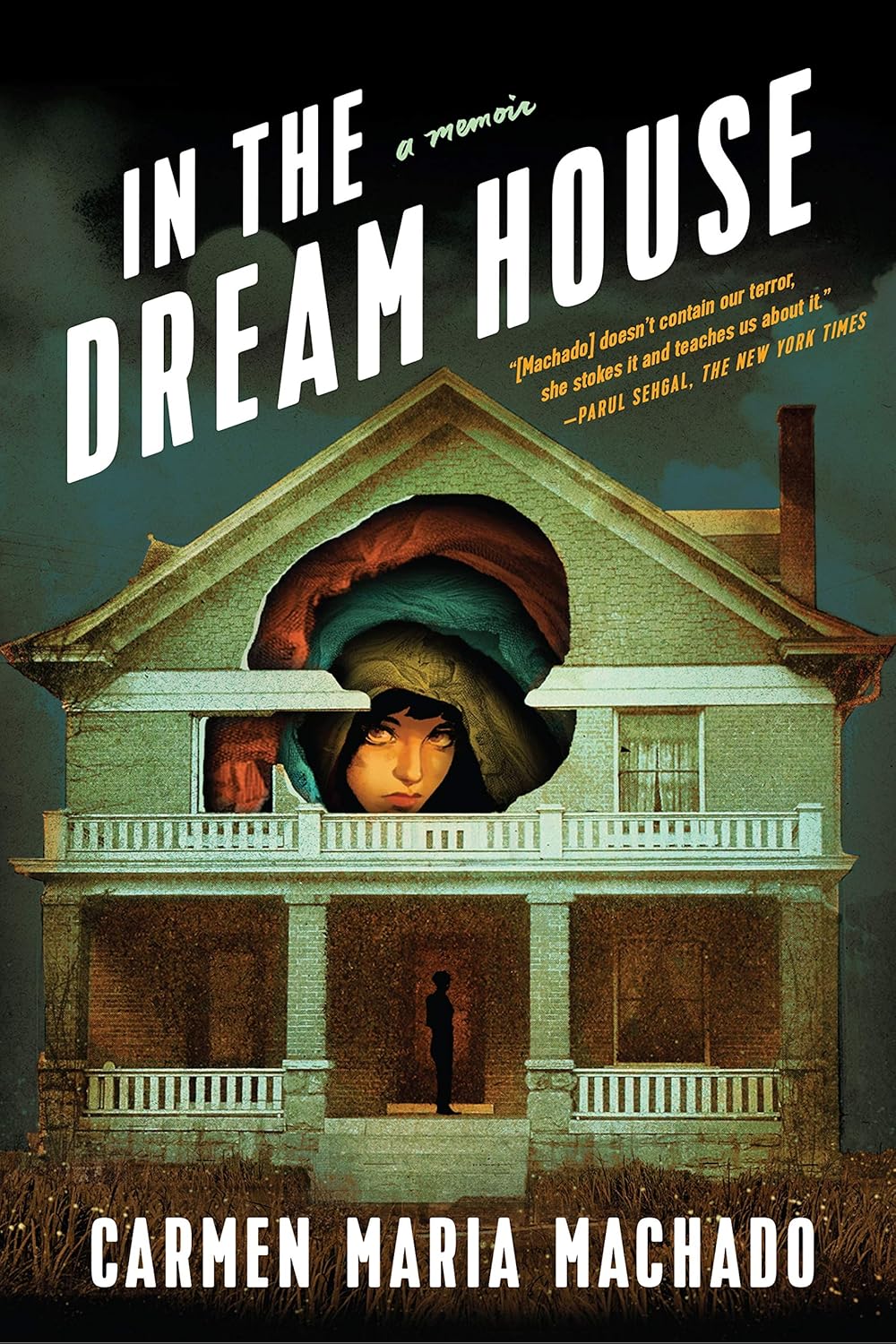

In the Dream House

Carmen Maria Machado

Graywolf Press, 2019, 272 pages

$26.00

Reviewed by Allison Quinlan

Content Warning: Abuse

My first encounter with Machado’s In the Dream House was when I worked in domestic abuse services and research. One of the women I was speaking to described what she had survived and asked if I had read Machado’s work; she shared a segment from the book to describe her experiences. The book gave her the words to describe what happened and what she needed to help her healing process, and I remember thinking, “This is something I should read.” This story is non-fiction. This narrative is Machado’s lived reality. Her recount is powerful, both in its content and in its presentation. She splits the narrative between ‘I’ and ‘You’ (‘I’ being the author now and ‘You’ being the author during the abuse). Suddenly, you’re reading about emotions and situations that ‘you’ experience as a victim-survivor, and empathy becomes ingrained.

She avoids explicit details of the abuse, but is clear about her survival of sexual, physical, emotional, and psychological violence. The woman in the dream house (the abuser) can be both exceptionally ‘loving’ and, the next instant, violent and terrifying. This duality mirrors the complicated realities of intimate partner violence (IPV): the person you love isn’t always bad all the time; it can be hard to realise a situation is abusive when you’re being love-bombed between the violence. Machado is clear—having survived and writing this from the perspective of someone who escaped—that no matter how ‘good’ an abuser can seem at times, it never excuses their abuse.

Lesbian IPV often goes unrecognised by both support services and survivors themselves, in part due to misalignment with heteronormative scripts of abuse (cis male abuser/cis female victim: white, thin, physically abused). Machado writes, “Putting language to something for which you have no language is no easy feat” (156), and rightly explains how even within the queer community, gender rhetoric has been used as “a way of absolving queer women from responsibility for domestic abuse” (230). She shares the story of Debra Reid, a Black lesbian woman who killed her abuser in self-defence (see the Framingham Eight). Reid’s case was reframed as ‘mutual battering’ and her sentence was never commuted like those of all the other women in the Framingham Eight. Machado concludes, “Narratives about abuse in queer relationships—whether acutely violent or not—are tricky in this same way. . . Our culture does not have an investment in helping queer folks understand what their experiences mean” (161).

There is also the complexity of reporting abuse in the queer community: Machado reiterates concerns about reinforcing negative lesbian stereotypes by sharing her experiences. She writes about this complication, noting, “queer does not equal good or pure or right. It is simply a state of being—one subject to politics, to its own social forces, to larger narratives, to moral complexities of every kind” (51-52). When reflecting on the abuse, she muses on what she’d say to her abuser: “For fuck’s sake, stop making us [lesbians] look bad” (145). The reality is that abuse can exist in all relationships, and if we avoid speaking out about it, it continues to go unaddressed, unexplored, and leaves queer communities vulnerable.

Machado’s work is incredibly important, but readers should be aware that the content can be difficult at times. This difficulty doesn’t mean you shouldn’t engage, but I would encourage readers to make sure they have space to work through any issues that may arise while reading. If any of the content mirrors your relationship or experiences (current or past), or if something doesn’t feel right in your relationship, reach out to a number below. Contacting doesn’t mean you’re in an abusive relationship, but it never hurts to speak to someone about an experience you feel uncomfortable with. Your feelings and experiences are real and deserve respect, validation, and support. Your partner(s) should respect you and make you feel safe.

Help is available:

RAINN (US): 800 656 4673

Lada Nacional Gratuita (MX): 800 822 4460

Canada Crisis Lines

Galop (UK): 0800 999 5428

1800Respect (AUS): 1800 737 732

WAVE Helplines (EU): 116 016

Allison Quinlan is a former support service provider and current PhD student working with adult LGBTQ+ survivors of IPV in Scotland.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven