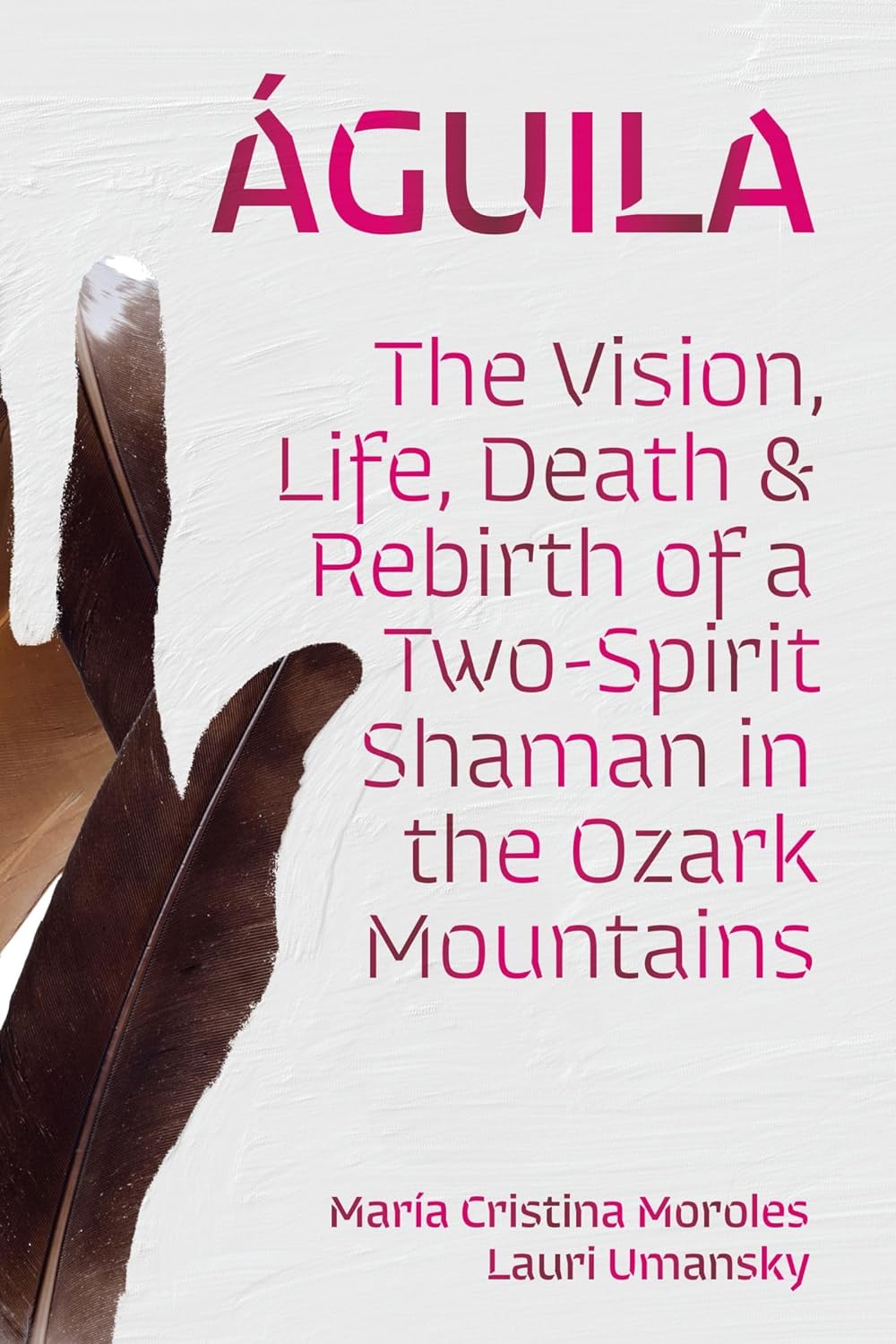

Review of Águila: The Vision, Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Two-Spirit Shaman in the Ozark Mountains by María Cristina Moroles and Lauri Umansky

Águila: The Vision, Life, Death, and Rebirth of a Two-Spirit Shaman in the Ozark Mountains

María Cristina Moroles and Lauri Umansky

The University of Arkansas Press, 2024, 208 pages

$24.95

Reviewed by Rose Norman

“Always remember that you are proud. You are proud first because you are an Indian; second because you are a Mexican; and last, because you are an American.” With these words, María Cristina Moroles’ father sent her off to first grade in Dallas, Texas, adding this warning: “They are going to say things to you. Do not ever believe them.” Having crossed the border undocumented twenty-seven times, José Moroles knew hardship but did not anticipate just how hard those Dallas schools would be on his oldest daughter, who quickly learned how to fight and not back down.

Raped at twelve, giving birth at thirteen, in foster care and on the Dallas streets thereafter, María Cristina Moroles overcame many obstacles before dying and being reborn as SunHawk in the Ozark mountains. Along the way, she had a conventional marriage to a man and a daughter Jenny whom she kept with her through subsequent adventures (having given up the rapist’s baby for adoption).

Her life took a turn for the better when she left her husband after following a vision from Texas to Fayetteville, Arkansas. There, she worked as a truck driver for an all-woman food co-op near a women’s land collective called Sassafras. Then, a local hepatitis epidemic brought her sick and dying to Sassafras, against her explicit wishes. Sassafras is where she died and was reborn as SunHawk.

SunHawk and another woman of color, Leona Garcia, were only twenty-three when the Sassafras women voted to give them the rugged land on the mountain next to them, 120 rocky acres accessed by an overgrown and deeply rutted logging road. This property would become Arco Iris, Rainbow Land, later Rancho Arco Iris, and finally Santuario Arco Iris, a sanctuary for women and children. Over time, many things changed. Leona left, other women and children came and went, some of them partners, but SunHawk remained. Always living gently and in sympathy with that rugged earth, SunHawk was not in good relation with the Sassafras women or her straight neighbors. She writes, “these mountains have harbored some women’s drama” (75). But she stuck it out, eventually making peace with her “archenemy,” Diana Rivers, who owned the neighboring Sassafras land and wound up giving those 450 acres to the nonprofit land trust that SunHawk had set up for the purpose of sustainability. After that, through another spiritual journey, SunHawk became Águila, or eagle, her shaman name and highest rank as a shamanic healer.

This memoir tells a special story, an important one to be told in these days when the earth and humanity are in great need of healing. It is a complicated story, full of earth magic and visions and healing energy. When I interviewed SunHawk in 2014 for Landykes of the South (Sinister Wisdom 98), our transcribed two-hour phone interview took many drafts to produce a short essay about the Arco Iris story. Lauri Umansky, Águila’s co-author for this book, transcribed fifty hours of interviews followed by years of back-and-forth revision. In an Afterword, Umansky describes the process and does not attempt to name the genre of this first-person memoir. This is not an “as told to” story, and Umansky is no ghostwriter; her name is on the title page, along with Águila’s birth name.

It is an artfully crafted story combining narrative, poetry, and prayers, and including a photo essay about the death and green burial of an old friend who came to Arco Iris hoping to be healed, and ultimately to die.

Above all, it is a story of resilience and healing on women’s land. We have few books about women’s land communities. This is an important one.

Rose Norman is a retired professor of English at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, where she co-founded the Women’s Studies program and was its first director. She later chaired the English Department. After retiring, she co-founded the Southern Lesbian Feminist Activist Herstory Project and is its general editor.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven