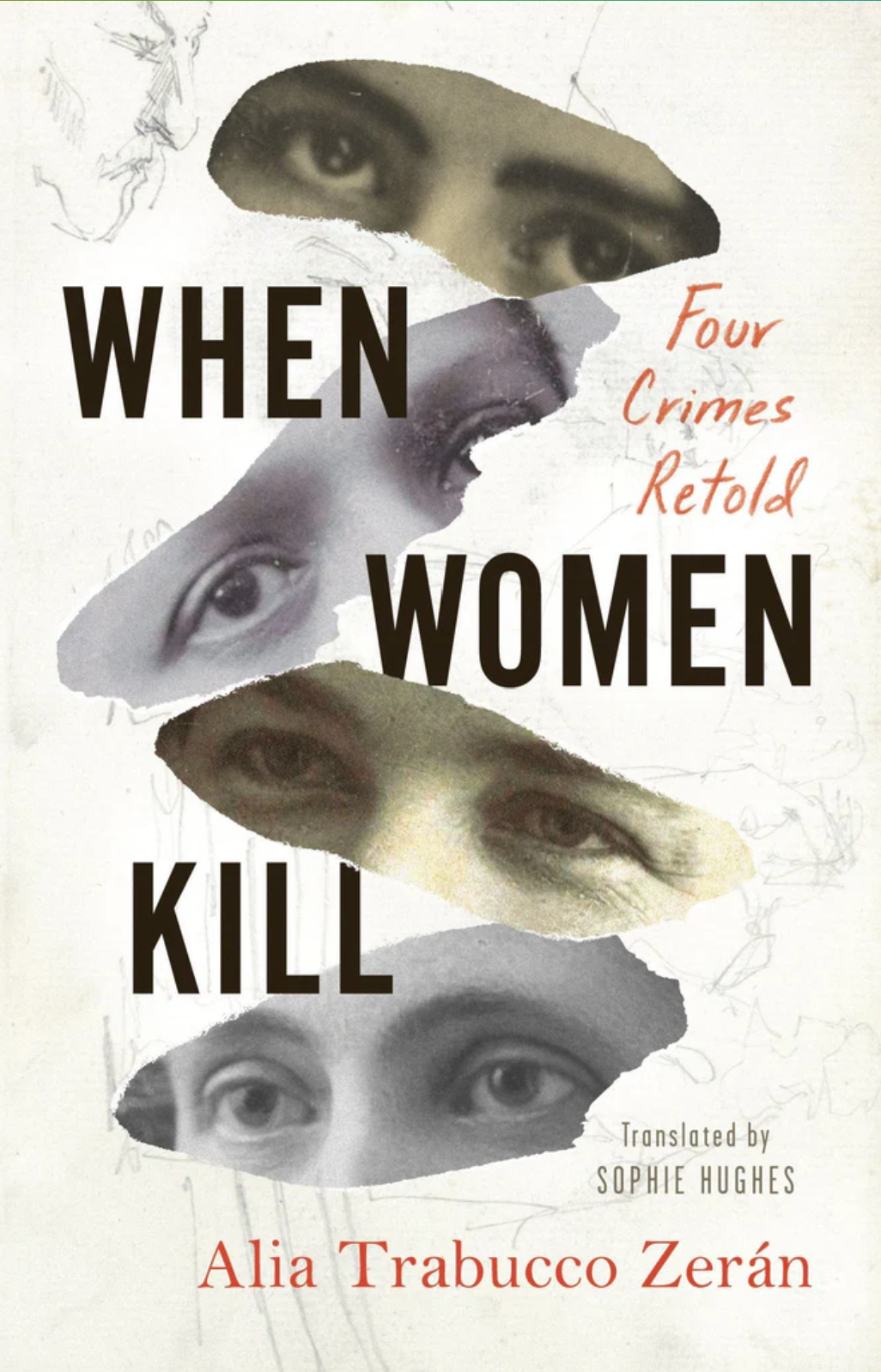

Review of When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold by Alia Trabucco Zerán, translated by Sophie Hughes

When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold

Alia Trabucco Zerán, translated by Sophie Hughes

Coffee House Press, 2022, 256 pages

$16.95

Reviewed by Henri Bensussen

Alia Trabucco Zerán grew up in Chile and decided at a young age to be a lawyer. She graduated from law school in spite of the barriers against women. She also knew she wanted to write. With a Fulbright scholarship, she earned a master’s at NYU in creative writing in Spanish. Her first book, a novel, was shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize in 2019 and was translated into seven languages. In When Women Kill, she searches for facts but, along the way, explores alternative forms of fiction.

Delving into the lives of four Chilean women who committed murder, she researches old files and any other sources that provide the clues she’s looking for. She discovers how these women were portrayed by the press, quotes their statements, considers their motivations, shows how their cases were presented to the court, and the scope of their verdicts and sentencing. Trabucco Zerán acts as a detective, uncovering clues and evidence long buried. She presents her findings to the reader as a story written from a feminist viewpoint. She brings in her own thoughts and experiences to link these stories, not only to their own time but to ours as well. It was as entertaining and informative as reading a literary, engaging mystery. Like a good mystery, each woman’s story ends with a surprise.

Trabucco Zerán began this project wanting to know how these women were “treated, viewed, construed, depicted.” Were their trials fair? What happened after being found guilty? She wants to retell their lives to a modern audience and try to make sense of their history. Murder is a common problem in Latin America, she says, so she was surprised that when she talked to people about her project, she was often misunderstood. It was “easier for people to imagine a dead woman, than a woman prepared to kill.”

Women killing doesn’t happen. “For a man. . . violence even helps confirm his masculinity.” To remember women who dare to be bad is a “task of feminism.” She wants to “expand accepted ideas to include men who don’t base their masculinity on violence and women who express rage without having themselves portrayed as somehow less human.”

She selects four women of the twentieth century whose acts incited the most extreme reactions in Chilean society and draws parallels between them and feminist history. None of these women were executed; they served relatively short times in jail or prison. Why? As Trabucco Zerán realizes, if a woman is less than human, then she is incapable of the kind of violent acts that are done by men. Each of the women described in this book was sentenced to death or long prison terms by lower courts but pardoned or given shorter sentences at top-level ones.

In 1916, aligned with the first wave of feminism, Corina Rojas hired a man to murder her husband. Accused of adultery as well as murder, a “double transgression against both the law and her gender,” the newspapers turn it into an act of love and passion. Small chapbooks are published that change Rojas from a criminal into “any old woman who now laments her crime.” A movie is made based on these stories, but censors do not allow its showing; a movie about a woman transgressor—it would not reflect well on Chile. Her lawyer appeals to the President of Chile to spare her life. And so, it is spared; she is freed after six years in jail.

In 1923, news vendor Rosa Faúndez Cavieres slaughtered her lover, which raised fears about women who worked, especially in a man’s job. Faúndez Cavieres was defended as a “defective woman and in no way comparable to. . . docile, feminine wives.” Discovering her husband had given her week’s wages to his mistress, she literally wrings his neck as he lies in a drunken stupor. She cuts up his body and drops pieces along a river. The court judged it a case of jealousy and sent her to a women’s prison staffed by nuns for twelve years. While there, she incites a riot when denied a cup of coffee. Seven decades later, she “reappears as The Lady Ripper” in a play, The History of Blood, that echoes the killings that happened under the military regime that overthrew Salvador Allende. “Lady Ripper is no longer the feared masculine killer of 1923. . . but instead the equally terrifying femme fatale.”

In 1955, when women won the right to vote, the writer María Carolina Geel shot the man who wanted to marry her after they ordered tea and cake at a popular hotel. She had not planned it, she says, she herself felt unhappy. She admits to the murder but refuses to provide a motive, she refuses to answer the question posed by the court: “Who are you?” Doctors and psychiatrists can’t agree on a motive. Her lawyer presents it as hysteria, a momentary madness. About to be freed, she publishes a story about jailed women-loving women. She wants to control her story, writes Trabucco Zerán, and not be described as “mad.” Amid the response to the story, the Court of Appeals sentences her to three years in prison. A letter from Gabriela Mistral, Chile’s Nobel prize winner, asks that Geel be pardoned, and she is. Geel spends only one year in jail.

In 1963, the “decade of women’s sexual liberation,” María Teresa Alfaro, a servant and nursemaid to three children, poisons them and their grandmother because she herself was not allowed to marry and had been forced to endure abortions. She was angry. The judge would not accept that a servant could be angry at her employer and sentenced her to death for the act of jealousy. The Court of Appeals reduced that to nineteen years in prison; she was released for good behavior after ten.

Trabucco Zerán points out that newspapers and photographs supported the courts in their attempt to “chasten. . . the insubordinate woman.” Judges didn’t want to turn women killers into martyrs or saints by putting them in front of a firing squad. She calls us to “incorporate the disobedient woman into our history.” Female violence requires that we question gender norms, the “invisible gender laws that equate femininity with weakness and submission.”

Henri Bensussen writes on themes of inter-personal/inter-species relationships, aging, and the comic aspects of the human condition from the viewpoint of a birder, biologist, and gardener. Currently, a book-length memoir is her focus, and she continues to publish poetry and creative non-fiction.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven