Review of Unsuitable: A History of Lesbian Fashion by Eleanor Medhurst

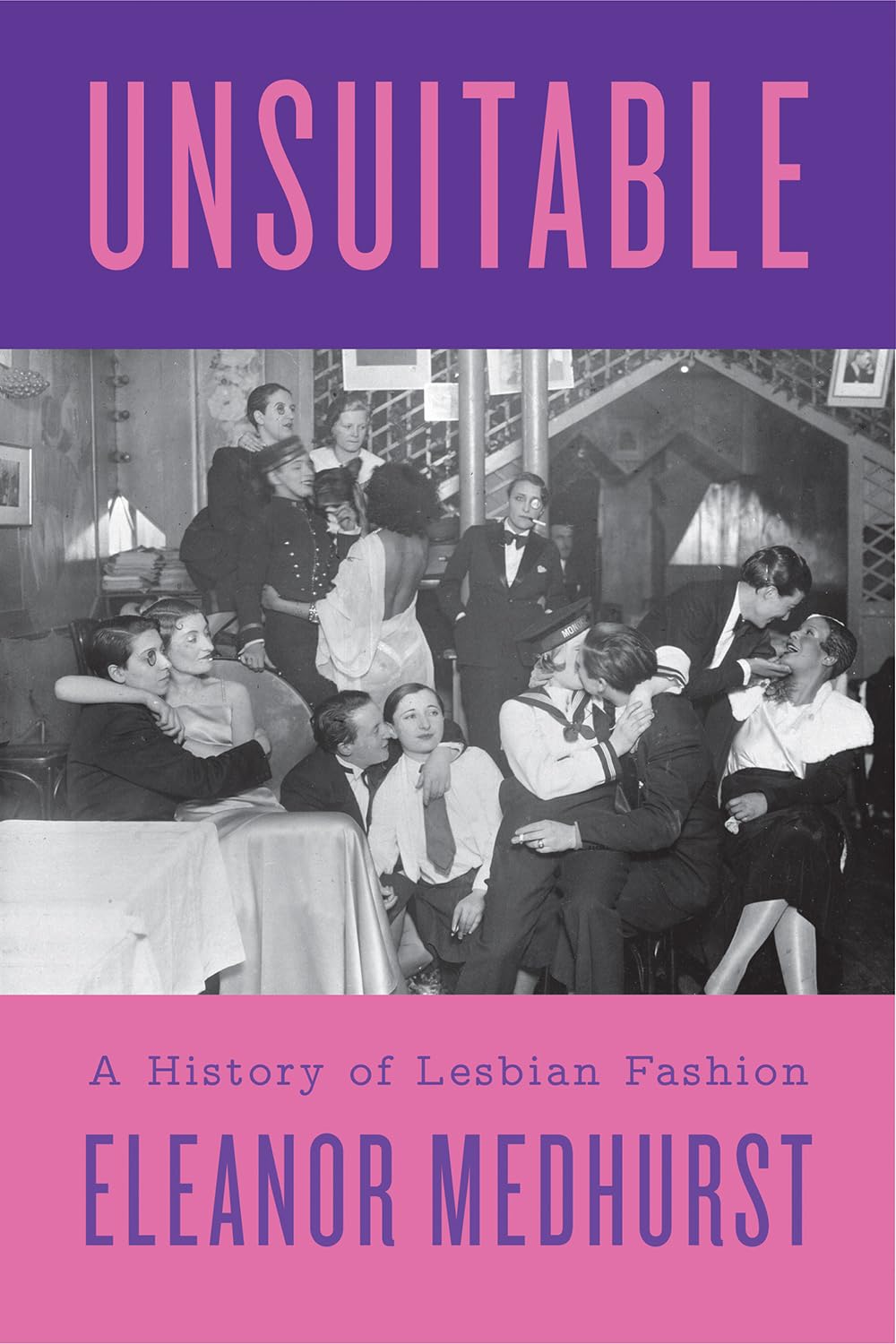

Unsuitable: A History of Lesbian Fashion

Eleanor Medhurst

Hurst, 2024, 344 pages

$34.95

Reviewed by Gabe Tejada

Unsuitable is a fitting title for fashion historian Eleanor Medhurst’s debut. As Medhurst illustrates, lesbian fashion—regardless of where it falls on the masculine-feminine spectrum—has always been transgressive. Throughout the book, we see how the donning of the lesbian closet’s unsuitable clothing is almost always penalised. Though far from a comprehensive history of lesbian fashion due to its geographical limitation (a more suitable subtitle would be A History of North American and European Lesbian Fashion, With a Brief Layover in Japan), Unsuitable remains an accessible and important introduction to lesbian sartorial history.

The book begins with the trinity of European lesbian historical figures: Sappho, Queen Christina of Sweden, and Anne Lister. Though their inclusion is integral in showing that “We Were Always Here,” these chapters almost make the emptiness of pre-1900s lesbian history starker and highlight how western-centric lesbian history is. This centering is ameliorated in the section’s chapter on 1910s Japan, our first glimpse of lesbian fashion’s ties—through the literary publication Seitō —with feminist politics and a broader lesbian community. By wearing the more masculine “umanori hakama” (the first iteration of Japanese girls’ school uniform, later replaced by the more feminine “andon hakama”) Hiratsuka Raichō, Otake Kokichi, and their Seitō society assert both cultural and gender/sexual identity, proving that one need not be sacrificed for the other. Medhurst shows how these garments were a revolt against the patriarchal ideal of the “ryōsai kenbo” (‘good wife, wise mother’)” (48), which emerged as education was opening up for Japanese women.

Part two pays homage to the 1920s, and though the chapters could have benefited from showing how the different locales’ (Britain, Paris, Berlin, and New York) fashion zeitgeists influenced each other, Medhurst nonetheless illuminates the immense contributions of lesbians to fashion—within and without their community—through the promotion of gender subversive styles in literary magazines. Lesbian fashion was literally in British Vogue. And publications like Frauenliebe and Die Freundin testify that trans identity and experience have always been a part of lesbians’—and their clothing’s—history.

The butch-femme interlude, unfortunately, left more to be desired. While Medhurst recognised that butch-femme dress codes went beyond expression and “were a means to express community and difference, push and pull, attraction and competition” (118), she did not delve into how these clothes were worn, touched, and presented in a manner unique to butches and femmes. Clothing was foundational to the courting rituals of the mid-century lesbian bar, and readers are left wanting for Medhurst’s insights and opinions on this phenomenon.

Those incensed by how undervalued and underappreciated drag kings’ artistry is will revel in “Miraculous Masculinity.” Here, we understand breeches’ roles and how other forms of male-impersonation performance art flourished in the UK and eventually in the US. Medhurst also captures how Black artistry and resistance went hand-in-hand, in the latter half of the section dedicated to Gladys Bentley and Stormé DeLarverie. Structuring Bentley’s chapter around excerpts from “I Am A Woman Again,” Medhurst acknowledges the cultural and socio-political climate during which Bentley penned the essay and recognised—without bitterness and without letting the piece eclipse the bold bravery of Bentley’s legacy—that Bentley had the right to protect herself amid growing hostility and persecution of queer people. Readers will also appreciate how Medhurst renders DeLarverie in sartorial three-dimensionality, “her stage self, her street self, and her softer, personal self” (157). In each iteration, we see DeLaverie’s determination to live—as much for herself as for her beloved queer community.

Sartorial choices in feminist/lesbian movements are akin to donning a suit of armour. From the suffragettes campaign for (some) women’s right to vote, to the different positions people took during the lesbian sex wars, fashion has always been wielded in the battle for rights. Fashion was a means of putting theory to action, like the androgynous “dyke uniform” meant to remove the “materially manifested gender hierarchy” (182). Medhurst also shows how t-shirts on dyke bodies are more than just a declarative statement, but a record of how lesbians made spaces for ourselves. Unsuitable weaves a powerful story of a lesbian fashion past that leaves readers hopeful for the future.

Gabe Tejada is a writer and reader based in Naarm/Melbourne whose work has been published in Archer Magazine and Kill Your Darlings, among others. His greatest achievement thus far is his 800-day Duolingo streak.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven