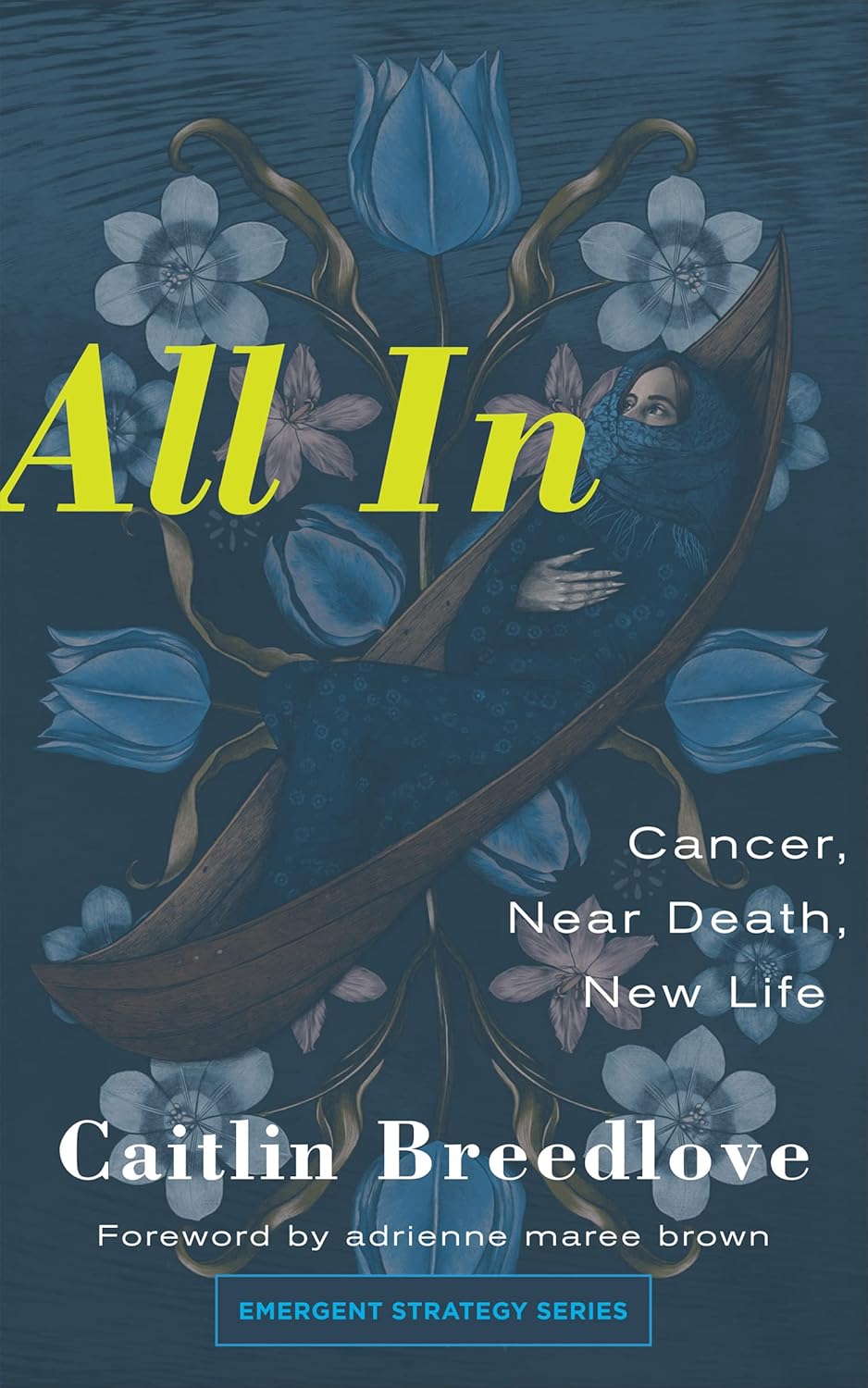

Review of All In: Cancer, Near Death, New Life by Caitlin Breedlove

All In: Cancer, Near Death, New Life

Caitlin Breedlove

AK Press, 2024, 152 pages

$18.00

Reviewed by Margaret Zanmiller

Caitlin Breedlove’s All In delivers a raw experience of an often ignored queer woman’s perspective concerning an ovarian cancer diagnosis. The memoir follows Breedlove from winter 2021 to autumn 2022, though readers are occasionally transported to Breedlove’s life before her diagnosis and to moments with ancestors. Breedlove encourages us as readers, all experiencing a collective sickness, to understand the cycles of our lives, be in communion with our ancestors and community, embrace change, and move forward with radical honesty. We are living in a time when disability is becoming more common for the American people. Our institutions ignore COVID-19 and other mental and physical illnesses, and our support for the disabled community wavers. Breedlove shares her experience with disability, working against persistent erasure.

Breedlove writes for mothers, queers, immigrant daughters, those passed on, and those surviving with cancer (27; 119). Stories from people like Breedlove fight against the traditional expectation to erase sickness and death from Western culture and discourse. Through engagement with stories such as Breedlove’s, change and suffering become a little more approachable simply because we no longer feel we are doing it alone. Breedlove notes the small number of books about cancer written by and for oppressed individuals. Breedlove, in the personal process of becoming a ‘filled bowl,’ is filling a collective bowl with her story. She approaches her story of cancer and near death with care, love, and empowerment. She adds new and collective tools to dismantle the masters’ house. For example, her descriptions of pain and near-death help to dismantle the white supremacist ideals of perfectionism and individualism (Okun, 2021) we typically find in books written by white women with cancer.

Themes of this chronology include motherhood, queerness, and Eastern European spirituality and culture. Readers searching for depictions of motherhood in all its pain and glory, the safety and healing of queer communities, and the beautiful simplicity of spirituality should be pleased with this book.

Towards the end of the book, Breedlove addresses her repetitive approach to writing; she states that this repetition reflects her natural state of forgetfulness that comes with sickness and opioid usage (95). I think the book’s repetitive nature also emphasizes a necessary approach to our collective struggles. Our brains and, often, our social status protect us from hearing what invokes change. We are rightfully rehearing and repeating congruent lessons. This (un)learning furthers our ability to be intersectional and non-binary in our thinking. Each lesson relearned directly challenges our individualistic comfort, our collective comfort, and our regime’s stability. The institutions around us, the systems that rule the Western world, work tirelessly to erase our stories and our progression. They encourage the disregard and silence surrounding our stories. Breedlove chronicles herself. She writes fully in her life, body, mind, and spirit.

Overall, Breedlove’s story is not just her own, but our collective experience with an oppressive state demanding overwork, overproduction, and silent death. She uses a refreshing writing style that inspires acceptance and confidence. In this book, readers sit with the reality of our collective sickness, the power of our stories, and our ability to be reborn alongside the ever-changing world.

Margaret Zanmiller is a Saint Paul dyke with a BA in Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies from the University of Minnesota.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven