Georgie Marsh Interviews Eleanor Medhurst

Interview with Eleanor Medhurst on Unsuitable: A History of Lesbian Fashion

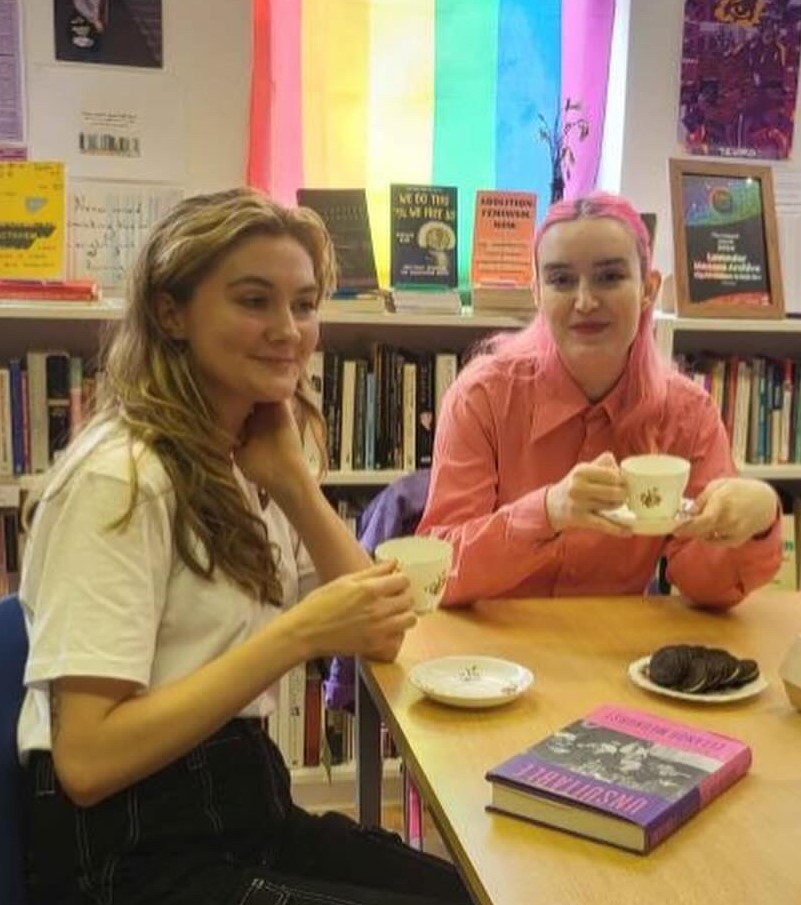

Georgie Marsh interviewed fashion historian Eleanor Medhurst at the Lavender Menace Queer Books Archive in Edinburgh during her book tour for Unsuitable: A History of Lesbian Fashion. You can read Lavender Menace’s portion of the interview here, where our community co-ordinator Keava McMillan asks Eleanor about her experiences working with archives as a fashion historian and how it influenced her work. You can also read Darla Tejada’s WSLR review of Unsuitable here. My interview is more focussed on fashion and lesbian style, particularly femme fashion history.

Eleanor described the journey she’s been on with her career, which began with posts on social media, including Instagram and TikTok, and her blog Dressing Dykes. On these social media platforms, she posts accessible snippets of the research she shares on her blog. This began after she did an undergraduate degree in Fashion and Dress History and a Master’s in History of Design and Material Culture. Aware of the gaps in the research, Eleanor did a lot of work during her Master’s related to lesbian and queer fashion in history. She started the blog to share the research that she did during her studies, which included looking at clothes worn by historical lesbian Anne Lister and at lesbian slogan t-shirts. Describing herself now as very much an independent researcher, Eleanor’s studies led to the publication of her book, Unsuitable.

Georgie Marsh: Do you have a personal style icon?

Eleanor Medhurst: My personal style icon! Honestly, I don’t really know if I have any one particular style icon. I wear a lot of pink, as you can see, and that’s just something I’ve been doing for many, many years now. I notice that I do bring influences in from my research, and I do consciously try and incorporate things into my own wardrobe and my own outfits. Someone who I do admire and who appears in my book is Natalie Barney, who was a very wealthy lesbian. She was an heiress and a writer, and she dressed in whatever she wanted at any point, which I think is just so fun. One of the stories that appears in the book is her housekeeper talking about how she would wear these white couture Madeleine Vionnet dresses. She would host her literary salons and would exist in the centre of these very lesbian-centric spaces wearing these fabulous white dresses; always different, but always a white Vionnet dress.

Georgie: Do you consider yourself to be someone who dresses for the female gaze, as opposed to the male gaze?

Eleanor: Yeah, definitely, I’ve never dressed for men in my life. I think that a lot of the subtleties that many queer women in particular do with their clothes, especially when dressing in more feminine ways, are things that women in general might pick up on. For example, I think women are more likely to see a woman dressed completely in pink and wonder why they are doing that, whereas, obviously it’s a bit of a generalisation, but I don’t think many men would look at it in this way. They’re more likely to just think, “well, she clearly likes pink.” So, definitely, yes, I’m only ever dressing for women! I’m also reminded of a quote by Mabel Hampton when she talks about her partner Lilian Foster, who was a very feminine lesbian. There are two quotes that go together; one is, “she was a feminine type of woman, she loved to dress” and the other is, “she never cared for men,” and I think those go hand in hand.

Georgie: Was there a particular person you found the most fun to write about in your book?

Eleanor: Natalie Barney, who I mentioned, was so fascinating to write about and again, any of the stories told by Mabel Hampton, just because they had so much personality behind them. I really loved writing about Stormé DeLarverie—I’ve got a whole chapter on her. She had such a fascinating life and the clothes she wore illustrate her life, but at the same time, they aren’t at the centre of it, which I think is an interesting way to look at lesbian fashion. Gladis Bentley is another male impersonator I loved writing about.

Georgie: Do you have a favourite moment in femme fashion history?

Eleanor: A favourite moment in femme fashion history! I’m not sure, I do think that the typical femmes of the mid-century bar scene deserve some more recognition on their own. I’ve got a whole section in the middle of the book about butch and femme, but I do think that often you’re looking through the lens of butch and femme together. From a lesbian perspective, we often look at butches and butch fashion because those are the people who were dressing in ways that were different and that they were often socially persecuted for. For this reason, I think that that’s a really important area to look at, because these butches in the wider world don’t get that recognition, especially in fashion. But I think that the clothes that femmes were wearing during that period and the ways that they were very intentionally styling themselves as part of a lesbian community, again for female gaze, is really important. It wasn’t just dressing in a conventionally feminine way; in many cases it was dressing in a lesbian feminine way—there were often specific codes of feminine dress that were in use in particular contexts in particular bars. I think that’s a very important area of femme fashion history.

Georgie: I know last night [at your book launch event] you mentioned wanting to research more into colour symbolism, which I’m really interested in as well. I wondered if there were any other specific areas that you had in mind for research in the future?

Eleanor: As you said, I’m starting to do some research into queer colour in general and queer uses of colour just because colour comes up so much in queer visual culture and fashion. Something that I really would like to do going forward is to look at lesbian fashion from more of a global perspective, and look at the ways that lesbian—or ‘lesbian-adjacent,’ to use a term that I use in the book—identities have been styled in so many other contexts across the world. This is something that I really want to commit to researching going forward because it will take a lot more time. I need to know about the context of a particular time period in a particular country in a particular community and it takes a lot more background research. I also need to find out about what was going on for lesbians, or whatever kind of identity or label people might be using, and then what was going on in fashion in general, so there are many more steps, but it’s something that I want to commit to researching going forward and hopefully reaching out to other people who might be looking at similar areas and working with them.

Georgie: So, have you started working on your new book?

Eleanor: Yes, but not very much. I haven’t written anything yet; I’ve been doing some research and working on it. I’ve written a proposal for it but I haven’t written any of the book, but I had to put that out of my head when I started doing the book tour. I finished the proof edits for this book in January, so I had a little bit of time to do some more research and do some other things. Since then, I’ve been doing book events, and I can’t think about anything else currently as I don’t have any space in my head!

Georgie: Do you have any advice for people who want to experiment more with how they present themselves but are a bit less confident? Secondly, what advice would you give to queer women specifically who felt that they had to reject conventional femininity when they came out to feel queer enough (which I felt a little bit at first), but now they realize that they want to embrace their femininity a bit more?

Eleanor: My advice for anyone who wants to experiment with dressing in any way that they don’t necessarily feel super comfortable in is to dress that way in a space that you feel safe or secure in to start with. I think that’s also something that’s reflected in lesbian history as well, with people bringing their preferred outfits to a club or a party for example, when they didn’t feel safe wearing them on the street. I think that especially if you’re going somewhere you feel safe and there are people who you’re friends with in a particular space, they’re more likely to hype you up and say, “yeah, I love this look!” which helps to slowly build your confidence.

For queer women who maybe felt like they had to dress in less of a feminine way—that’s also something that appears time and time again in lesbian history. Anyone who’s feeling like that is very much not alone in it. I think that it’s important to feel comfortable in what you’re wearing and feel like you’re representing yourself in the way that you want to be represented. I think it’s just important to remember that femmes, feminine lesbians, and feminine queer women have always existed, have been really important members of the community, and have been appreciated for the ways that they have dressed and presented themselves. You’re just as queer as anyone else!

Georgie: Thank you so much! Is there anything you’d like to add or something you hope people will ask you?

Eleanor: I just enjoy talking to different people and hearing different questions that people have, because ultimately we all have to choose what we’re wearing—we all have to get dressed—and we all have such a personal relationship to the clothes that we wear, which is why I think it’s such an important lens to view social histories and marginalized histories with, because it says so much about the kind of people wearing the clothes. So it’s really nice to have discussions about clothes and fashion history and lesbian fashion history with different people whose questions are coming from different places!

Georgie Marsh conducted this interview on April 7, 2024.

Georgie Marsh is an English graduate and current MA student in Sexual Dissidence based in Brighton. In her spare time, she writes blogs for LGBT Health & Well-being and volunteers with the digital community archiving project Queer Heritage South. She loves animals, reading, Chappell Roan, and drag shows.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven