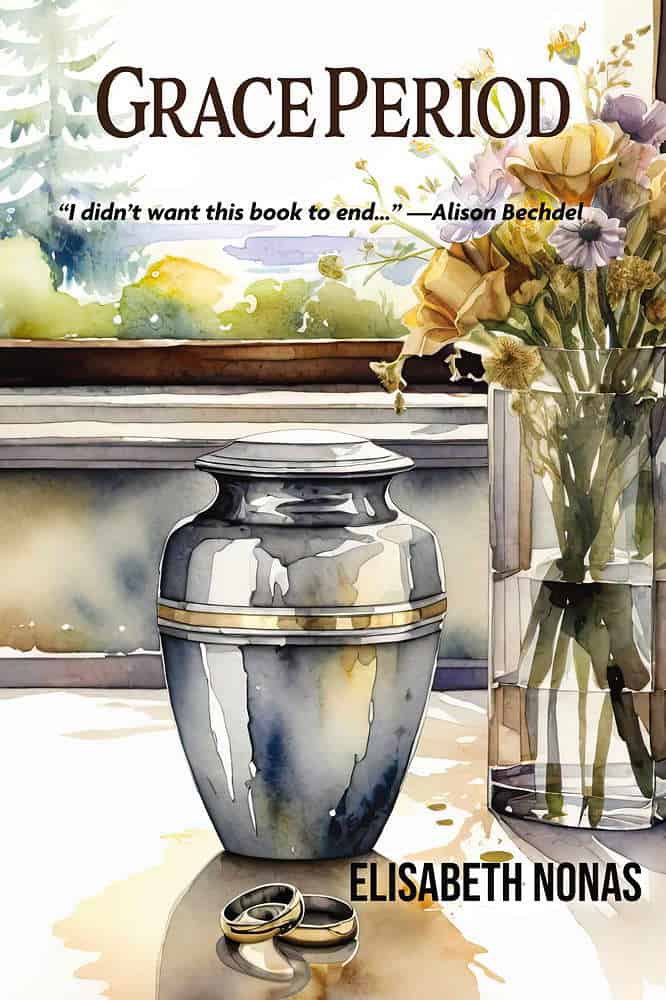

Review of Grace Period by Elisabeth Nonas

Grace Period

Elisabeth Nonas

Rattling Good Yarns Press, 2024, 286 pages

$18.95

Reviewed by Judith Katz

Elisabeth Nonas’ lovely fourth novel, Grace Period, starts with a funeral—and a standup comedy act. The funeral is for Grace Black, an art history professor at a small college in Ithaca, New York. The comedienne filling us in on the details of the funeral is Grace’s partner of 25 years, 70-year-old Hannah Greene, who is on the edge of retiring from her position in the English department of that same college.

Grace was ten years Hannah’s junior. She died of a stroke on the way to Hannah’s retirement party, just weeks away from the start of her sabbatical. Going back and forth in time, Hannah traces the stories of her past and present life with Grace and the dashed hopes of what was to be their future. She spends the bulk of her grieving (and this novel) trying to figure out who she is and what she is meant to do now that Grace is gone.

Nonas has created an affable first-person narrator with Hannah. She’s a funny and self-deprecating Jewish butch whose sartorial choices run to polos, tees, shorts, and sweats.

Grace was the cook in the family and the gardener, too. When left to her own devices, Hannah feels lost in the beautifully appointed kitchen the couple designed together to meet Grace’s exacting specifications. Days into her grieving, Hannah is barely able to make herself a cup of espresso as she finds herself at odds with a newfangled coffee maker clearly purchased by Grace before her accident. Hannah can’t even figure out what to eat for dinner or, once having done that, how to prepare it.

Friends reach out, offer dinner and coffee dates, and even suggest she get a dog. But Hannah seems committed to her isolation. To establish some order in her life, Hannah begins to consult the imaginary Grace for advice about what to do next. She makes lists and slowly begins to follow them, heating up soup and eventually getting herself to eat it.

Hannah’s isolation doesn’t last for long. A few days after the funeral, a dusty Subaru, like the one Grace used to drive, roars up to the house. Out pop Cristina, the new instructor to the Art History department that Grace had hired, and Nicole, her lover. Unaware of Grace’s death, the two are caught off guard, but Hannah graciously offers them a temporary place to stay with the caveat that she won’t be very good company. The women reluctantly take Hannah up on her offer, and she seems to reluctantly welcome them in.

All the while, Hannah struggles to find solid memories of her life with Grace. Yes, there are souvenirs of their various trips together, like a particular bottle of wine that lets her reminisce. But none of these things seem sufficient. It isn’t until she finds herself cleaning out Grace’s office at the college where they both worked that Hannah finally stumbles onto evidence of something concrete that raises a memory. It’s precisely the kind of recollection a surviving partner would much rather forget, and yet, this hint of an event (which may or may not have happened) is exactly the thing that eventually brings Hannah toward a real sense of grieving and the core of her love for Grace.

Judith Katz is the author of two novels, The Escape Artist and Running Fiercely Toward a High Thin Sound, which won the 1992 Lambda Literary Award for Best Lesbian Fiction. She is currently working on sequels to both novels, and is still meditating on her novel in a drawer, The Atomic Age.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven