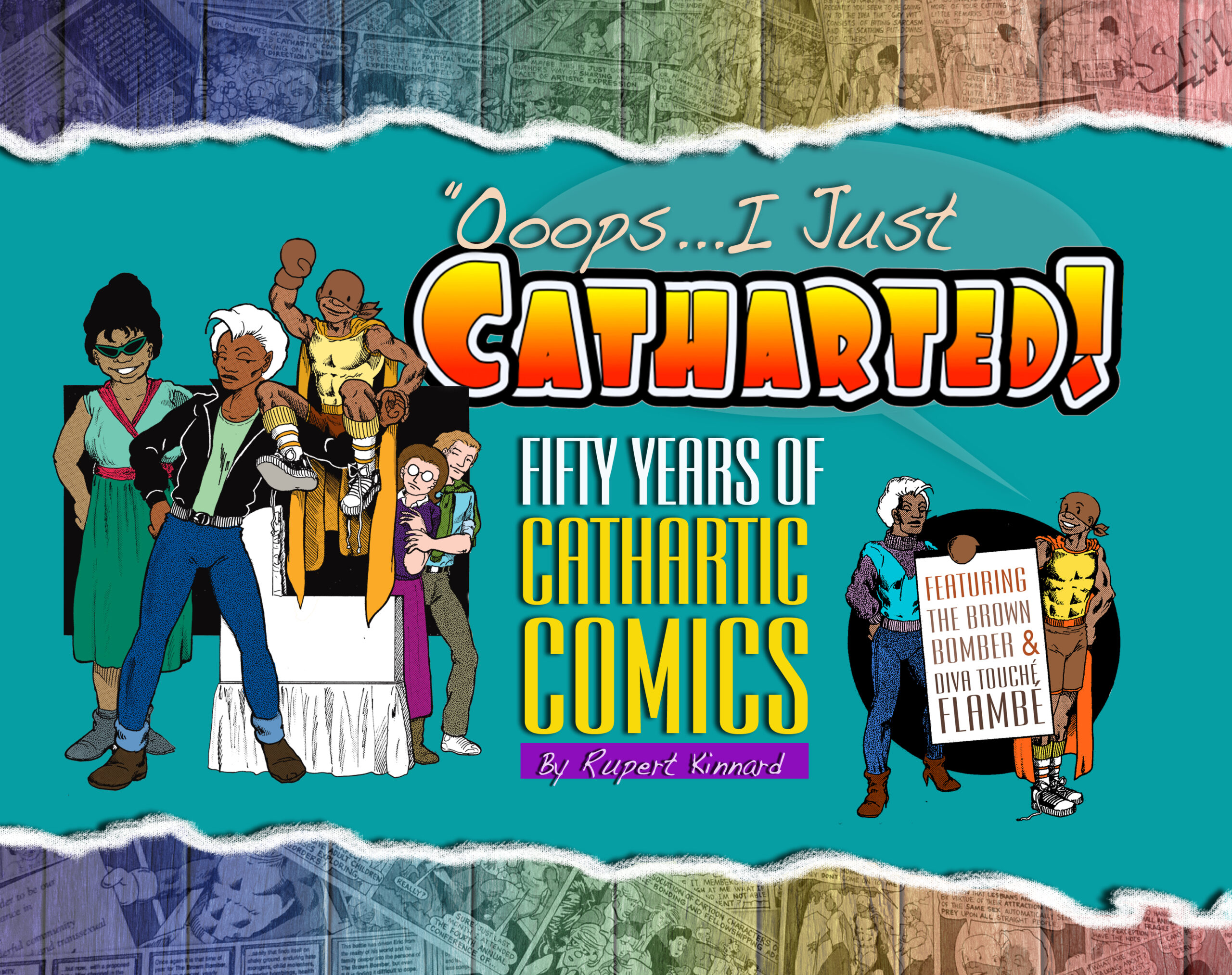

Ooops…I Just Catharted! Fifty Years of Cathartic Comics

Rupert Kinnard

Stacked Deck Press, 2025, 278 pages

$34.95

Reviewed by Julia M. Allen

Allow me to introduce to you Professor I. B. Gittendowne, otherwise known as Rupert Kinnard, the creator of the first Black gay and lesbian comic strip. The strip ran for over twenty years in a variety of alternative and queer periodicals, and now, Kinnard has collected these pointedly hilarious gems into a beautifully designed and produced 11 ¾” by 9 ¼” hardcover volume: Ooops…I Just Catharted! Fifty Years of Cathartic Comics. Beginning with his first cartoon character, the Brown Bomber, Professor I. B. Gittendowne deploys the most effective and universally available persuasive tool—humor—to topple racist, sexist, and homophobic absurdities. The four-panel strip grew to feature two inimitable main characters: the Brown Bomber and Diva Touché Flambé. Perpetually nineteen years old, the Brown Bomber (named after boxing champ Joe Louis) is an endearingly innocent, buff, single-gloved, non-violent gay superhero; his side-kick, Diva, is a Ph.D.-holding lesbian educator—honoring, Kinnard tells us, the many strong, intelligent women in his life. Together, the two create a depth of social analysis and action that could not have been achieved by a single character.

In 278 lavishly-illustrated pages, Kinnard tells the story of how he developed the strip over the years. A native of Chicago, Kinnard began his artistic career as a student at Cornell College, a small liberal arts school in Mt. Vernon, Iowa. At first, the strip’s only regular character was the Brown Bomber (B.B.), who appeared in the weekly student newspaper, addressing various institutional problems. B.B. was joined at times by the Vanilla Cremepuff, a barely disguised college president, viewed askance for clueless inaction on racial issues. After three and a half years—and wildly-successful campus Brown Bomber T-shirt sales—the Brown Bomber came out as gay.

After graduating in 1979 and moving to Portland, Oregon, Kinnard began publishing Brown Bomber strips in a short-lived local gay and lesbian newspaper, the NW Fountain. A few years later, the Brown Bomber began gracing the pages of a new queer publication, Just Out, where he was soon joined by Diva Touché Flambé, who offered transformative visions and actions to assuage the Brown Bomber’s dismay at the irrationality he often encountered. In addition to occasionally displaying certain mystical powers when nothing else would suffice—e.g., turning an unrepentant LA police officer into a pig—Diva introduces a therapeutic device called slapthology, promoting clear thinking in the recalcitrant with a slap upside the head. “Wow!” says a character, post-slap, “My mind feels as fresh as a breath mint! I guess most written history has centered around the accomplishments of white people!” Kinnard reflects, “I saw myself as being part Diva and part Bomber.”

A job loss in Portland led Kinnard to move to the Bay Area, where Cathartic Comics flourished in the SF Weekly, an alternative paper, for seven years. During this time, Kinnard reinvented his author persona as Prof. I. B. Gittendowne. When the SF Weekly changed hands, ending that paper’s run of Cathartic Comics, Kinnard returned to Portland. Kinnard’s involvement in a life-changing car accident brought the weekly strip to a close, but did not alter the enthusiasm of his fan base or change Kinnard’s dedication to the persuasive use of art and humor as an avenue to social justice. We can only be grateful that he has spent his recent years compiling and designing this celebration of B.B. and the Diva.

Ooops…I Just Catharted! features hundreds of Cathartic Comics strips which otherwise would have vanished along with the newsprint on which they appeared. The artistry is superb, every panel full of energy as characters interact with each other and react to their world’s latest outrages. The Brown Bomber almost always looks the same—wearing the same tennis shoes and over-sized athletic socks, the same shorts, same cape, same boxing glove on his right hand, same scarf tied on his head. The elegant Diva, however, rarely wears the same outfit twice.

In the text accompanying the strips and other illustrations, Kinnard describes both his choices of drawing tools and his artistic and graphic design education. He narrates the development of Cathartic Comics from his childhood to 2025, providing explanatory detail for strips that comment on events with which some readers may not be familiar, such as Ronald Reagan’s gaffe during the 1988 Republican National Convention when he tried to say, “facts are stubborn things,” but actually said, “facts are stupid things.”

Occasionally, I found myself losing the thread of the narrative text as I immersed myself in strip after strip from a given era. Later, I discovered two compact chronologies near the end of the book. I’d suggest that readers look at these first for an overview, then read from the beginning. I should also add that some typos, misspellings, and punctuation errors have crept into the text, but, while unfortunate, they do not lead to misreadings.

Ooops…I Just Catharted! offers hours of joyful reading, just when we need it.

Julia M. Allen is Professor Emerita, English, Sonoma State University. She is the author of Passionate Commitments: The Lives of Anna Rochester and Grace Hutchins, SUNY Press, 2013 and co-author with Jocelyn H. Cohen of Women Making History: The Revolutionary Feminist Postcard Art of Helaine Victoria Press, Lever Press, 2023.