Review of Still Life by Katherine Packert Burke

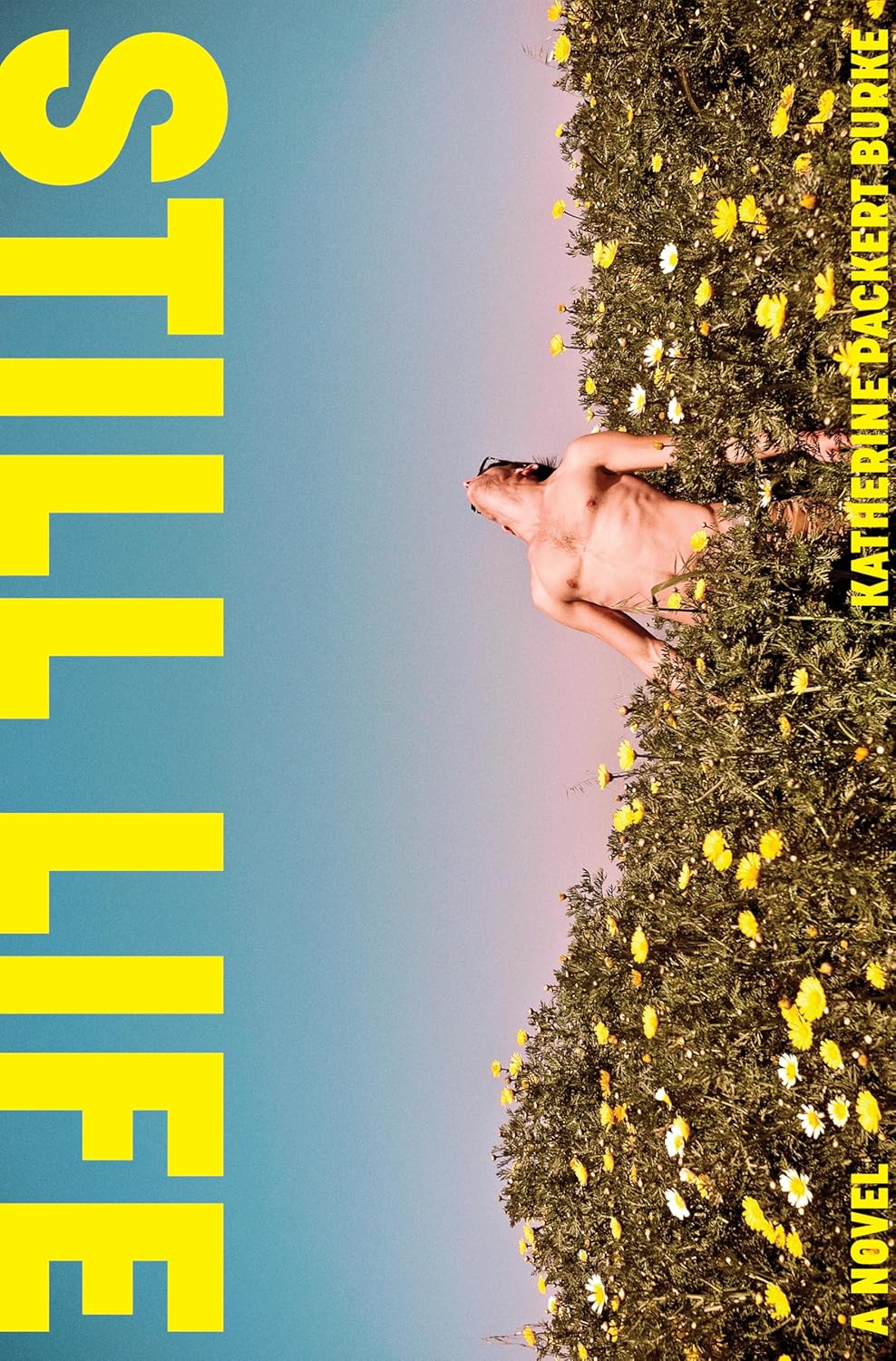

Still Life

Katherine Packert Burke

Simon and Schuster, 2024, 272 pages

$28.99

Reviewed by Catherine Horowitz

Still Life, Katherine Packert Burke’s debut novel, is a heartfelt, candid, sometimes overcomplicated, always authentic, and ultimately singular tribute to queer friendship and relationships. Its main character, Edith, is a writer in her late twenties returning to Boston for the first time since living there for a few years after undergrad. Boston holds old friends, old haunts, an ex-girlfriend, and memories of a life she feels both removed from and still stuck in. The book moves between Edith’s visit and life back at home in Texas, and her memories of college and the years directly after.

The structure works well, moving back and forth between past and present in a way that generally feels seamless and purposeful. The present often feels trancelike and strange, while the past feels real and vivid. Dialogue is written in italics throughout both past and present, making the past feel not so distant and the present feel as blurry as a memory.

The three main characters, Edith, her ex, Tessa, and Valerie, their friend from college who has since died in a car crash, are clearly written with care and love. Many books attempt the challenge of authentically capturing what it is to be a young queer person alive in the twenty-first century. It’s a difficult thing to convey, but Burke does it beautifully.

Edith, Valerie, Tessa, and their friends all feel very real; they talk about things I talk about and act like people I know; they have similar interests, similar conflicts and feelings, and are frustrating in similar ways. I grew to feel real concern about Edith, and frustration at how stuck in her feelings she was. I was fond of Tessa’s Boston lesbian hangouts, with all their irritating characters, silly activities, and oscillation between belonging and not. I wanted to know exactly how these characters changed and what ultimately happened between them, which is revealed gradually and strategically throughout the first part of the book.

The second part of the book follows Edith’s current life in Texas alongside her evolving relationship with Valerie while in grad school. Valerie is a little less tangible as a character than Edith and Tessa, although she still felt recognizable. This, along with the absence of the first half’s clear trajectory, might be why this section was harder to become invested in.

I also initially found Still Life compelling because of its use of Sondheim, Edith’s personal soundtrack that she often uses to analyze her own life. Burke mainly references two musicals, Merrily We Roll Along and Into the Woods. The parallels to Merrily are obvious and articulated poignantly. Both works follow the trajectory of a group of three friends, ultimately explaining how their relationships become fractured and unrecognizable from how they began.

Into the Woods isn’t as clear. I truly understand the impulse to incorporate it, a cathartic classic for theater kids during lonely times, into one’s work. But Burke struggles a little to articulate its thematic connections to Still Life, instead complexly weaving lyrics and summary into the narrative. I wonder whether its use is effective for those who aren’t Sondheim lovers like me.

The theme of autofiction presents another intriguing throughline in Still Life. Edith is initially apprehensive of autofiction and hesitant to admit that she is working on it. She reflects on the genre, continuously reevaluating her work and ultimately writing the first line of Still Life itself, unsure of what it will lead to. This discussion may be meant as a sort of meta-reflection on autofiction, or an attempt from Burke to account for her own misapprehensions about it. I might not have read Still Life as autofiction otherwise, and even if I had, I wouldn’t have thought as heavily about the genre’s shortcomings while reading. I’m not sure whether this was Burke’s goal, but it warrants interesting conversation.

Despite its sometimes tangled themes and storylines, Still Life is mesmerizing, profound, and will stick with you. I find myself thinking back to the characters, and wondering whatever became of them. I can imagine a neater version—maybe one that ended after Edith left Boston—but at the same time, this version, messy, imperfect, and a little cumbersome, has its own kind of authenticity and beauty.

Catherine Horowitz is a writer and educator living in Washington, D.C. She earned a B.A. in English and Jewish Studies from Oberlin College. You can find her other work in Bright Wall/Dark Room, New Voices, and the Jewish Women’s Archive. She has previously worked with Sinister Wisdom on A Sturdy Yes of People: Selected Writings by Joan Nestle.

"Empowerment comes from ideas."

― Charlene Carruthers

"Your silence will not protect you."

— Tourmaline

"Gender is the poetry each of us makes out of the language we are taught."

— Leila Raven