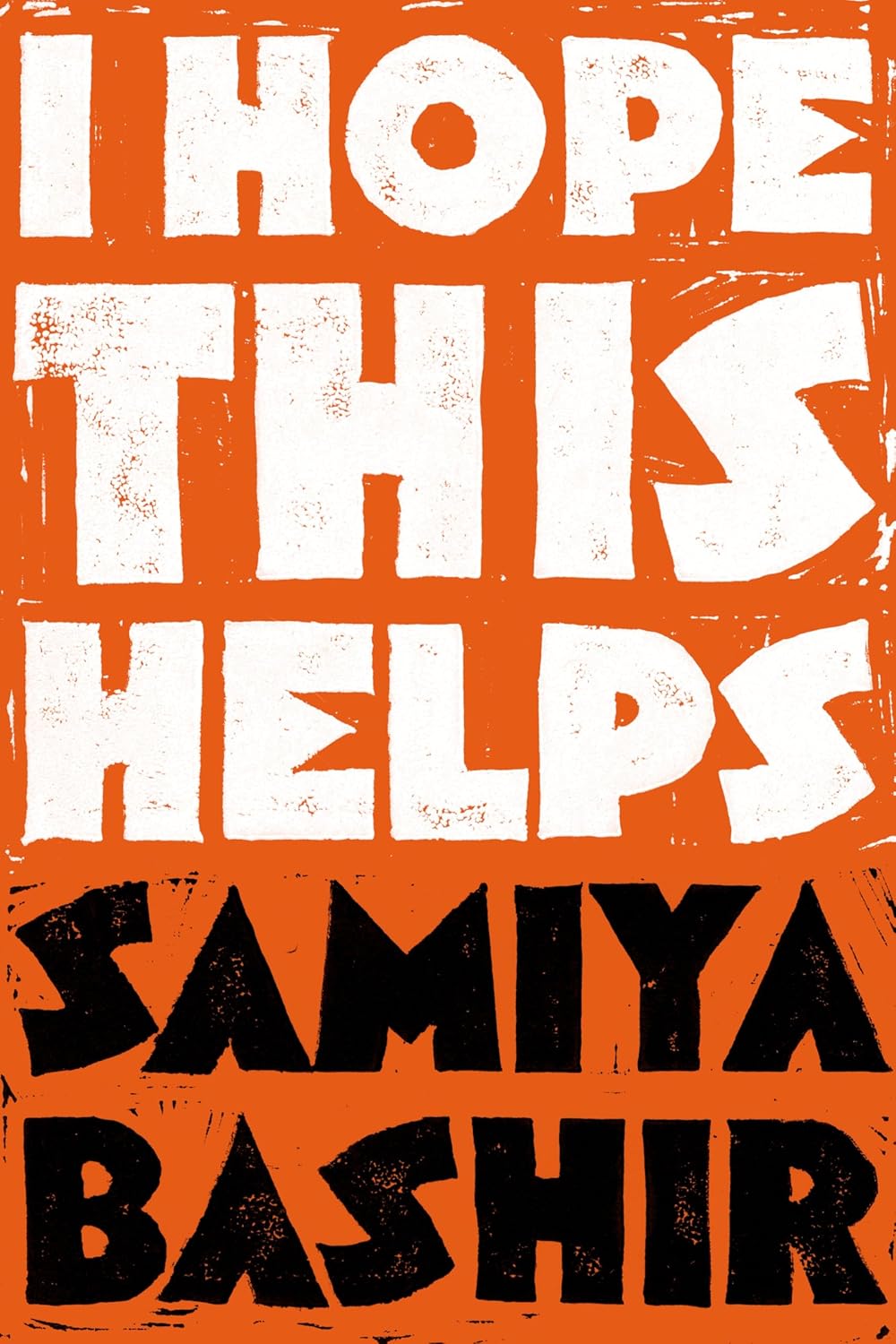

I Hope This Helps

Samiya Bashir

Nightboat Books, 2025, 144 pages

$18.95

Reviewed by Beth Brown Preston

Seven years after Field Theories—Samiya Bashir’s third poetry collection which won the 2018 Oregon Book Award for Poetry—comes her recent work in I Hope This Helps. Bashir’s work, both individual and collective, has been published, printed, and performed across America and abroad. Samiya Bashir is a poet, librettist, performer, and multimedia artist. Her honors include a Joseph Brodsky Rome Prize in Literature, a Pushcart Prize, Oregon’s Regional Arts and Culture Council Individual Artist Fellowship in Literature, and two Michigan Hopwood Poetry Awards. She currently serves as the June Jordan Visiting Scholar at Columbia University.

Bashir has edited magazines and anthologies of literature and visual arts. In 2002, she cofounded Fire & Ink, an advocacy organization and writer’s festival for LGBTQ+ writers of African descent. Also, she served as an executive director of Lambda Literary from 2022 to 2023 where her mission was to elevate the work of LGBTQ+ writers, affirm the value of their stories, and advocate for queer and trans writers.

I Hope This Helps explores the metamorphosis of the artist despite the despair brought on by isolation and the limits of our social realities: time, money, work, and widespread global crises. Her poems raise the question: “What can it mean to thrive in the world as it is?” Both within and extending beyond traditional academic settings, Bashir’s work creates, employs, and teaches a restorative poetics, turning her moments of painful experience into triumphs of witness, healing, and change. Her meditation reveals her vulnerable inner life and how she has evolved into an artist.

Bashir knew at the age of eight that she wanted to become a writer. She taught herself how to read early and started keeping a journal. Both of her parents were public school teachers. She was encouraged by her grandfather’s nephew, who was a journalist, to begin writing. Other early influences on her work were hearing June Jordan’s “Poem About My Rights” in 1991 and 1992, and the murder of Rodney King.

Subsequently, Bashir learned the importance of community among writers. She has said about the writer’s life: “If there's any utility to being a poet. . . it’s our job. To help people articulate what’s happening. And know they're not alone in the articulating of it.”

To Bashir, “The poem itself is something alive—not just existing on the page.” Bashir has invested time in the theater and her operas and installations have traveled throughout the country. “Awareness,” she says, “is the chief motivation to art. You can be distracted and miss it. We’re taught to be distracted.” We have been distracted from attention to the fates of certain populations. “When you’re talking to people of color you must have to acknowledge trauma.”

In I Hope This Helps, Bashir’s work benefits from her well-rounded artistic perspective. Her poems thrive in the form of typographies, cartographies, musical scores, and photographs (e.g. the poems “Negro Being” and “Freakish Beauty,” (102-103). Other poems in the collection draw on Bashir’s lifelong practice of journaling. The poem “Letter from Exile” highlights her sojourn in Rome after winning a coveted prize:

“I am still, in theory, one of two 2019-20 Rome Prize Fellows in Literature. The year marked the 125th anniversary of the American Academy in Rome: a rare two-poet year. Bold and brilliant Nicole Sealey holds the second prize.”

“We are, together, the Academy’s first Black women Literature Fellows. Ever. Being a Negro First™ just feels so last century” (50).

This prose poem startles the reader with its insistence that the poet’s stay in Rome under the auspices of the prize, during the pandemic, was a form of exile, an expatriate experience both physical and intellectual.

Of the Italian language she writes in the poem/journal:

“The Venetian etymology of ciao is one of enslavement. Whether coming or going one said schiavo: I am your slave. This was, I guess, in case someone forgot” (53).

And of her return to the States she writes:

“Most days America screams to anyone who’ll listen how it hates me so much it would rather kill us all than let me live” (55).

The poet Erica Hunt has written of this new collection: “What do we do to live and thrive—as Black people, joyous and queer, new neighbors and strangers, our full humanity—dwarfed in the shadows by towers of power, distraction, and fear? Bashir’s poetry leans into these questions using her superpower—pausing to listen—over-hearing and hearing over—‘hearing’ under and rewriting, reinscribing her Journey—through the ‘twinkle textured disco ball Jenga set’—and shows the reader how creative power fuels us to begin again. And again.”

Beth Brown Preston is a poet and novelist. A graduate of Bryn Mawr College and the MFA Writing Program of Goddard College, she has been a CBS Fellow in Writing at the University of Pennsylvania and a Bread Loaf Scholar. Her work has appeared and is forthcoming in many literary and scholarly journals.